| VOL XVI | OCTOBER, 1916 |

NO. 6 |

![]()

SHARKS—MAN-EATERS AND OTHERS.

![]()

With suggestions that Americans turn to economic account

some of the smaller species of the Atlantic Coast

![]()

By Hugh M. Smith

United States Commissioner of Fisheries

The unprecedented attacks by sharks on human beings along the middle Atlantic coast of the United States in the summer of 1916, resulting in the death of four bathers, produced a profound sensation and materially interfered with the attendance at seaside resorts, while leading to an astonishing amount of newspaper discussion in the course of which the public was regaled with more fiction and also more facts about sharks in general than ever before in our history. Several departments of the federal government became involved in the matter, various individuals and committees offered rewards for the capture of "man-eating" sharks, and a bill was introduced in Congress appropriating money for the purpose of enabling the Department of Commerce to coöperate in the extermination of man-eating sharks on the New Jersey coast.

The Bureau of Fisheries was incessantly importuned to explain why sharks were behaving as they were, and to take action that would prevent further attacks. There was some criticism of our inability to cope with the situation, although obviously there was little that could he done. The culprits were never identified. It was not known whether one individual shark of a species common to the region was running amuck; whether representatives of several local species had been forced to attack human beings because of certain undetermined biological or physical conditions; or whether there was an advent of a shark or sharks from distant waters with feeding habits different from those of the domestic species, which in no former years had exhibited any man-eating tendency and were dangerous only when they themselves were attacked.

There were no attacks reported after the middle of July and the scare subsided; but out of all the excitement and discussion there has arisen a keen lay interest in sharks—their kinds, habits, size, distribution, and economic value; and in answer to that interest there have been special displays in museums and publication of much authentic matter in the secular and scientific press. —Hugh M. Smith.

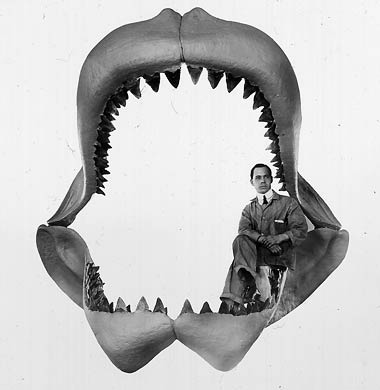

Great White Shark or Man-Eater, taken Off Palm Beach, Florida: This young twelve-foot specimen of the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) was taken by Mr. Sidney M. Colgate in December 1913, while out hunting sharks with Iris family. Man-eaters were not expected; other sharks generally succumb quietly when harpooned. This creature, however, when struck, turned and hit the wooden harpoon pole in two, attacked the launch with such vigor that it sprung a leak, and was only finally dispatched by several revolver shots. These sharks are characterized by large size and voracity, and by unusually large mouth and teeth, which render them very capable of man-eating, and circumstantial evidence also accounts for their sinister name. The maximum length attained is about forty feet, with teeth three inches long, but from the size of fossil teeth found it is thought that in the past individuals of the same genus (Carcharodon) must have attained a length of seventy to eighty feet [but see note 3]. The white shark inhabits tropical waters and is rarely found within fifty miles of New York. Courtesy of Mr. Sidney M. Colgate |

| ||

THE term “man-eater” is applied by the public to almost any shark of medium or large size, and during the recent scare any shark over five feet long was likely to be called a “man-eater” and recorded as such in the daily press. The writer saw a published photograph of a “man-eater” shark and its proud captor; assuming the height of the man to have been six feet, the shark could not have exceeded three feet in length. In fish literature the name “man-eater” is restricted to the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), known also as the great blue shark The name man-eater is justified, however, only by the large size, formidable teeth, voracity, and obvious ability of the fish to kill and eat human beings; it is certainly not warranted by a confirmed man-eating habit. (1)

While this fish occurs regularly, although not abundantly, in summer along parts of our coast where sea bathing is extensively indulged in, it must be regarded as comparatively inoffensive in our waters even if the recent fatalities on the New Jersey coast are attributable to it.

| ||

The genus Carcharodon reached its climax in the past, during the Eocene or Miocene, when fish immensely larger than any now existing must have roamed the seas. It has been thought that, because of the size of the fossil teeth (opinion of the late Dr. George Brown Goode), individuals seventy to eighty feet long must have been common. The model of the jaws of a shark of this genus in the American Museum of Natural History (see photograph below) suggests the colossal proportions attained in geological times. In these degenerate modern days the maximum length reached by the white shark appears to be about forty feet, with teeth three inches long. The British Museum contains the jaws of a specimen thirty-six feet long from Australia.(2) The gustatory feats that can be performed by fish of such size may be judged by the accomplishment of a thirty-foot individual on the California coast which had in its stomach an entire sea lion weighing one hundred pounds. The writer has before him a note on a shark of this species collected by a Bureau of Fisheries party at Menemsha Bight, Martha’s Vineyard, on August 19, 1916; it was twelve feet eight inches long, and more than five feet in girth at the pectorals, and was estimated to weigh one thousand pounds.(3)

In the same family with Carcharodon, and distinguished therefrom by having the edges of the teeth entire instead of serrate, are the mackerel sharks, of which four species may be found on the Atlantic coast (all of these are now placed in the genus Isurus by Garman; The Plagiostomia, 1913). One of these (4), a cosmopolitan species in temperate latitudes, is the “porbeagle” of England (Lamna nasus). It attains a length of ten to twelve feet. The common species on the east coast of the United States is the “blue shark” of the Cape Cod fishermen, readily distinguishable by the large black spot on the pectoral fin. It reaches a length of eight to ten feet. The mackerel sharks are handsome, trim, and active species, and are so named because they are present chiefly during the mackerel season and prey largely on that fish. They are sometimes very annoying to purse-seine, pound-net, and gill-net fishermen.

|

||

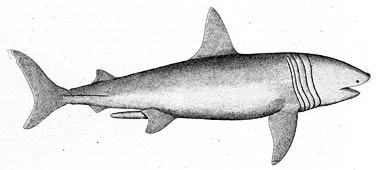

Related to the mackerel sharks anatomically, but differing markedly from them in habits and disposition, is the basking shark or bone shark (Cetorhinus maximus). These names have been applied by our fishermen in allusion to the facts that the fish often remains quiet at the surface for a long time and that the gill arches are provided with strainers which resemble whalebone. This fish was described by the Norwegian bishop Gunner in 1765 in a learned paper in which he sought to prove that this must have been the “great fish” that swallowed Jonah. From the standpoint of mere size, the basking shark fulfills all the requirements, for it is one of the largest of sharks and the ingestion of a prophet would have entailed no difficulty or inconvenience. A length of fifty feet has been claimed for it, but the available authentic records give a maximum of under forty feet. It is at home in the Arctic seas, but sometimes has strayed as far southward as Virginia and California. In former years it was not uncommon on the New England coast and also on the shores of western Europe; and it was regularly hunted for its oil in Ireland and Norway. In the early eighteenth century, and in the early part of the last century, it was not infrequently harpooned by the Maine and Massachusetts fishermen, and the liver of a large specimen has been known to yield twelve barrels of oil. From Eastport, Maine, and Provincetown, Massachusetts, and even from the lower harbor of New York,

| ||

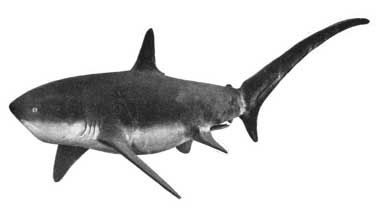

The thrasher or swingle-tail (Alopias vulpinus) is another large and active pelagic shark which is common along the coasts of New England and western and southern Europe, and is known also from California. It is at once distinguished from all other sharks by its prodigious tail (see photo below), the tipper lobe of which, in the form of a scythe blade, is half the total length of the fish. The fishermen tell tales of the ferocity of this shark in attacking whales, which, when they come to the surface to breathe, are said to be flailed by the thrasher’s flexible tail, so that the resounding whacks may be heard for several miles in calm weather. Authentic observations of this habit are lacking. The species is certainly harmless for man, in spite of its large size—it attains a length of fifteen feet and a weight of five hundred pounds. It is a source of some annoyance to our mackerel fishermen because it often becomes entangled in the nets. In July, 1904, an imperfect skeleton of this fish about ten and one-half feet long, with cranium and two hundred and seventy-four vertebrae, was exhibited at Atlantic City, as that of a “sea serpent,” and an impossible account of its capture was published in the local newspapers at the time (for identity of this skeleton, see note by the writer in Forest and Stream, December 3, 1904).

|

||

In strong contrast with the striking modification of the tail in the foregoing species, the hammer-head and the bonnet-head sharks (Sphyrna zygaena and S. tiburo), present grotesque lateral expansions of the head. Both species range from the tropics along our east coast as far as Massachusetts. The former is a voracious species and, attaining a length of more than fifteen feet, is formidable to man; the latter, much the commoner on our South Atlantic coast, rarely exceeds five feet in length. Mitchill’s Fishes of New York records the capture of three hammer-heads in a net at Riverhead, New York, September, 1805; the largest, eleven feet long, contained the detached remains of a man and also a striped cotton shirt.

The sand shark (Carcharias taurus) is one of the best-known sharks of our Atlantic coast. It is sometimes called “shovel-nose shark” and “dogfish shark” on the shores of New England. Its usual length is under five feet, but it is said, perhaps on account of error in identification, to attain a length of twelve feet and a weight of two hundred and fifty pounds. It is built on rakish lines, its snout is sharp, its crescentic mouth is armed with long and narrow teeth, the fishermen say it has a wicked eye, and its disposition is vicious. It is able to do very serious injury to careless fishermen who are trying to remove it from their nets or boats, and the writer has seen it inflict fearful wounds on other species of sharks confined with it in the observation pool at Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

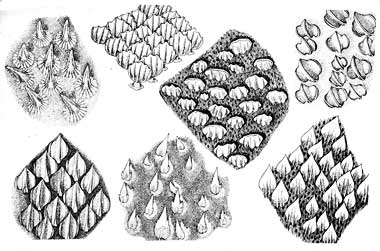

The largest family of sharks in our waters is the Carcharinidae.(5) The many genera however are not always easily distinguishable until the teeth and dermal denticles are carefully examined (see illustration below).

| ||

Two of the most interesting are the blue shark (Mustelus canis), a world-wide species attaining a moderate size, characterized by the very dark blue color of the upper parts; and the tiger shark, or leopard shark (Galeocerdo cuvier), an active, graceful, ferocious species, with razor-like teeth. The latter is known from Provincetown, Woods Hole, and other places on the Atlantic coast.(6)

Scientific names of fish are not always expressive of obvious habits or structure, but Somniosus microcephalus, or the “small-headed sleeper,” aptly describes a large boreal shark that makes occasional visits to our coasts as far south as Cape Cod and Oregon. Its body seems to have developed at the expense of its brain, for it is a sluggish stupid glutton that reaches a length of twenty-five to thirty feet. It is said to be a very active foe of whales. When caught in the fisheries of western Europe, the sleeper shark is brought in by the fishermen and offered for sale as food, although its market value is small. The writer has seen it in the markets of Grimsby, Cuxhaven, and Hamburg.

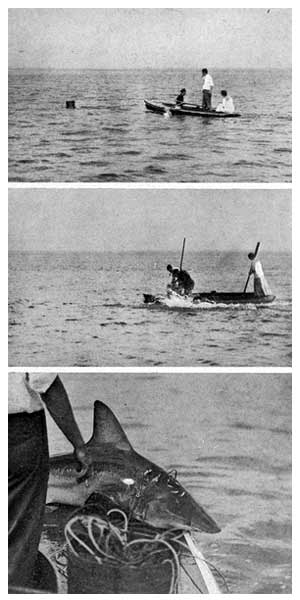

One of the rarest and at the same time most strongly differentiated sharks on the coasts of the United States is the cow shark (Hexanchus griseus), at once recognizable by its single dorsal fin, and its six gill apertures (see photo below). The dentition also is peculiar (in the front of the tipper jaw there are four pointed teeth, on each side of which are three with one or several cusps, and laterally the teeth have many cusps; while in the middle of the lower jaw there are a small tooth with or without a cusp, and lateral serrated teeth with many cusps). There appears to be only one instance of the occurrence of’ this shark in our waters, although it is said by Poey to be often found about Cuba. An individual ten feet two inches long was taken in 1886 at Currituck Inlet, N. C., a plaster cast of which is in the United States National Museum. On the shores of western and southern Europe, where the cow shark is most common, it attains a length of twenty-six feet or over.

|

||

Among the most interesting sharks of the world are the deep-sea species. The extreme depth at which sharks have been found is about one and one-sixth miles. The deep-sea forms are for the most part small, of a blackish or dark brownish color, and do not exhibit any marked structural differentiation from the littoral and pelagic species. There have been taken off the east coast of Africa and in the Gulf of Aden (on the “Valdivia” cruise), at a maximum depth of 1,006 fathoms, several specimens of a hitherto unknown shark (Apristurus indicus). The largest is thirteen inches long. This species inhabits a greater depth than any other shark, as far as known.(7)

One of the most striking of the deep-sea sharks is a form taken by the “Albatross” in Batangas Bay, Luzon, Philippine Islands, at a depth of one hundred and seventy fathoms (it was made the type of a new genus and called Squaliolus laticaudus by Smith & Radcliffe (see photo below). It is cylindrical, slender, with very narrow peduncle

|

|||

We have not yet spoken of the largest of all sharks—which means the largest of all fishes of the world. This is the “whale shark” (Rhinodon typus), originally described from Cape of Good Hope, but now known from India, Japan, South America, Panama, California, and various other places. There have been two individuals taken on the coast of Florida, the first, a rather small one (eighteen feet long) obtained at Ormond in 1902; the second a veritable monster, caught at Knight’s Key in June, 1912. The skin of the fish was stuffed in a distorted shape (see photo below) and exhibited in various parts of the country as “The Only Creature of the Kind in the World.” The advertised length of the fish was forty-five feet, but from the best information obtainable it was somewhat more than thirty-eight feet long before stuffing.

This shark has a very broad and obtuse snout and an exceedingly wide mouth armed with numerous minute teeth; the dark-colored body is marked with many small whitish spots. The species is stated to attain a length of seventy feet and is known to exceed fifty feet. Notwithstanding its immense size, however, it is harmless to man unless attacked, and feeds on the small creatures for which its teeth are adapted. Its huge bulk makes it dangerous in the same way that a whale is dangerous. Years ago it was reported that the sperm-whale fishermen on the island of Saint Denis, in the Indian Ocean, dreaded to harpoon a whale shark by mistake, and stories are told of how a harpooned fish “having by a lightning-like dive exhausted the supply of rope which had been accidentally fastened to the boat, dived deeper still, and so pulled a pirogue and crew to the bottom.”

|

||

The sharks most numerous on the United States coasts are the small forms known as dogfishes, which belong in two distinct families and get their name from their habit of going in droves or packs like wild clogs. The smooth dogfish (Mustelus canis), is one of the omnipresent fishes of the Atlantic coast in summer from Cape Cod to Cape Hatteras, and is abundant on the lower Carolina coast in spring. It is a slender graceful species, without spines in the dorsal fins, reaching a length of three feet, and having pavement-like teeth adapted for crushing lobsters, crabs, and other bottom-loving creatures. The horny or spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias) is found on both sides of the North Atlantic and is easily the most abundant and most destructive of our east-coast sharks. The spiny dogfish ranges as far north as the Gulf of St. Lawrence and south to North Carolina, and reaches its maximum abundance north of Cape Cod. Coming along our shores in schools containing untold millions, and one school following another often with slight intermission, these fishes do immense damage for fishermen by devouring or mutilating the food fish taken in the gill nets, by eating the bait and the line-caught fish, by chewing and tearing nets and lines, by filling pound nets to the exclusion of other fish, and by devouring lobsters in and out of the lobster pots. When the schools of dogfish appear, the fishermen must abandon their efforts, and the loss of fish and apparatus is thus supplemented by loss of time.

|

||

One of the great American needs at the present time is the shark-eating man. All sharks of sufficient size have a food value, and in many parts of the world sharks are regularly fished for and used for human consumption. In the United States the utilization of sharks has been negligible for several reasons; notably because of the abundance and variety of other food fish, and because of our ignorance of their food value, and our deep-seated prejudice on account of their unsavory reputation as consumers of the most promiscuous materials, including living and dead human beings. It may prove to have been a very unfortunate coincidence that the killing of Americans by sharks should have come at the very time when the Bureau of Fisheries was inaugurating a campaign to induce the wholesale consumption by Americans of one of the most destructive, though least dangerous, species of sharks. It remains to be seen whether, in spite of this untimely handicap, a movement in the interest of fishermen and fish consumers, based on indisputable economic facts, will not succeed.

The Congress of the United States, at the recent session, appropriated $25,000 to enable the Commissioner of Fisheries to conduct investigations and experiments for the purpose of ameliorating the damage to the fisheries done by the dogfish and other predacious fishes. The act is aimed primarily at the spiny dogfish, and the task before the Bureau of Fisheries is to convert an unmitigated nuisance into a valuable asset.

NOTES (except as otherwise noted, all date from 1916)

“White sharks are so scarce that their habits are little known, but they are said to feed to some extent on big sea turtles, biting off their legs and even cutting through their shells. Of this species it may he said that judging from its physical make-up it would not hesitate to attack a man in the water. . . . Even a relatively small white shark, weighing two or three hundred pounds, might readily snap the largest human bones by a jerk of its body after it laid bitten through the flesh. The occurrence of the white shark near New York being almost as unprecedented as the attacks on bathers which happened simultaneously, the capture of a specimen by Mr. Schliesser confirms our belief that the white shark was responsible for the casualties.”These views of Messrs. Nichols and Murphy are stated in full in the Magazine Section of the New York Times for August 6, 1916. —THE EDITOR.

On August 8, 1914, a small school of large tiger sharks appeared in the Fort Macon Channel near the fisheries laboratory and swam around the “Fish Hawk.” A baited shark hook thrown over the side was seized by the largest of the school. The line offered little resistance to this big fellow and he disappeared, taking bait and hook with him. During the time that elapsed while another hook was being secured and baited, the rest of the school came up under the stern of the ship, showing no fear of the men in the cockpit a few feet above them. Apparently the sharks were very hungry and were prepared to grasp anything that might fall to them in the nature of food. When the second hook was thrown over, it was seized by one of the school. This shark, which was killed and brought on deck, was eight and two-thirds feet in length. For the second time this hook was thrown overboard and soon another specimen, ten and one-twelfth feet in length was captured and hung from the end of the boom with its head out of the water. On the third cast, another, nine and one-sixth feet in length, was captured. About this time a shark, larger than any of those taken, swam up to the one hanging from the boom, and raising its head partly out of the water, seized the dead shark by the throat. As it did so, the captain of the “Fish Hawk” began shooting at it, with a 32-caliber revolver, as rapidly as he could take aim. The shots seemed only to infuriate the shark, and it shook the dead one so viciously as to make it seem doubtful whether the boom would withstand its onslaught. Finally it tore a very large section of the unfortunate’s belly, tearing out and devouring the whole liver, leaving a gaping hole across the entire width of the body large enough to permit a small child easily to enter the body cavity. At this instant one of the bullets struck a vital spot, and after a lively struggle on the part of the launch’s crew, a rope was secured around its tail. The four specimens, all females, were brought to the laboratory for examination. The last shark was twelve feet in length, and the liver of the smaller one was still in its stomach, the estimated weight of which was forty pounds.