Featured Story

![]()

October 2006

Sociable Killers

![]()

New studies of the white shark (aka great white) show that

its social life and hunting strategies are surprisingly complex.

![]()

By R. Aidan Martin and Anne Martin

|

The shark, an eleven-and-a-half-foot male we call Sneaky, circles back unhurriedly and seizes the hapless pup again. He carries it underwater, shaking his head violently from side to side, an action that maximizes the cutting efficiency of his saw-edged teeth. An ominous blush stains the water and the oily, coppery smell of the wounded seal prickles our nostrils. The seal carcass floats to the surface while gulls and other seabirds compete vigorously for its entrails, squawking avian obscenities at one another. Sneaky returns to his meal, and another white shark rises from below—a thirteen-foot male we call Couz.

|

Watching such ferocious predatory assaults and intense socializing is a shark biologist’s dream. In fact, despite the white shark’s reputation as the animal kingdom’s überpredator, surprisingly little is known about the basics of its foraging behavior: its hunting tactics, its feeding cycle, its preferences in prey. Its migration routes and favorite hunting grounds, aside from the waters around Seal Island and several other places, remain largely unknown. And even less is known about its social behavior. Most people—at least since the movie Jaws—assume the creatures are solitary, stupid, antisocial brutes. But after observing the white sharks at Seal Island for eight seasons, and documenting more than 2,500 predatory attacks, we have arrived at quite a different opinion. Our research demonstrates that white sharks are intelligent, curious, oddly skittish creatures, whose social interactions and foraging behavior are more complex and sophisticated than anyone had imagined.

Nowhere is that social and foraging behavior on more vivid display than at Seal Island, a rocky, five-acre islet in False Bay, twenty-two miles south of Cape Town. The island is home to some 64,000 Cape fur seals, plus thousands of cormorants, gulls, penguins, and other seabirds. Mother fur seals give birth here in the spring, around the end of December. By early May the pups are joining their older siblings on fishing trips into False Bay and beyond. That’s when the white sharks start showing up—from parts unknown—to hunt the young-of-the-year pups.

|

Chris Fallows and Rob Lawrence, South African naturalists based in Simon’s Town on False Bay, discovered the site’s attractions in 1995, when they observed the sharks’ vigorous seasonal predatory activity and their remarkable aerial hunting style. (Both behaviors can be observed elsewhere, but far less frequently than at Seal Island.) At Fallows and Lawrence’s invitation, we visited Seal Island in 2000 to see for ourselves. Since then we have returned each southern winter to continue studying the remarkable behavior of the white shark.

In the popular imagination, Carcharodon carcharias is the quintessential predator. The largest of all predatory sharks, it reaches a length of more than twenty feet and a weight of 4,500 pounds. The white shark possesses acute color vision, the largest scent-detecting organs of any shark, and sensitive electroreceptors that give it access to environmental cues beyond human experience.

As for habitat, the white shark prefers cool and temperate seas worldwide. Its brain, swimming muscles, and gut maintain a temperature as much as twenty-five Fahrenheit degrees warmer than the water. That enables white sharks to exploit cold, prey-rich waters, but it also exacts a price: they must eat a great deal to fuel their high metabolism.

The white shark’s diet includes bony fish, crabs, rays, sea birds, other sharks, snails, squid, and turtles, but marine mammals may be its favorite meal. Many of them are big, powerful animals in their own right, but predators with the means to catch them hit caloric pay dirt when they sink their teeth into the mammals’ thick layer of blubber. Pound for pound, fat has more than twice as many calories as protein. By one estimate, a fifteen-foot white shark that consumes sixty-five pounds of whale blubber can go a month and a half without feeding again.

|

How does a white shark decide what to eat? A model known as optimal foraging theory offers a mathematical explanation of how predators weigh the calorie content of food against the energetic cost of searching for it and handling it. According to the theory, predators employ one of two basic strategies: they seek to maximize either energy or numbers. Energy maximizers selectively eat only high-calorie prey. Their search costs are high, but so is the energy payoff per meal. Numbers maximizers, by contrast, eat whatever kind of prey is most abundant, regardless of its energy content, thereby keeping per-meal search costs low.

Based on optimal foraging theory, A. Peter Klimley, a marine biologist at the University of California, Davis, has proposed an intriguing theory about the feeding behavior of the white shark. According to Klimley’s theory, white sharks are energy maximizers, so they reject low-fat foods. That neatly explains why they often feed on seals and sea lions but rarely on penguins and sea otters, which are notably less fatty. As we mentioned earlier, however, white sharks eat many other kinds of prey. Although those prey may be low-cal, compared with sea mammals, they may also be easier to find and catch, and thus sometimes energetically more attractive. It seems likely that white sharks follow both strategies, depending on which is the more profitable in a given circumstance.

Of all marine mammals, newly weaned seals and sea lions may offer the best energy bargain for white sharks. They have a thick layer of blubber, limited diving and fighting skills, and a naïveté about the dangers lurking below.

| ||

Far from being the indiscriminate killers the movies have portrayed, white sharks are quite selective in targeting their prey. But on what basis does a shark select one individual from a group of superficially similar animals? No one knows for sure. Many investigators think predators that rely on single-species prey groups, such as schools of fish or pods of dolphins, have developed a keen sense for subtle individual differences that indicate vulnerability. An individual that lags behind, turns a little slower, or ventures just a bit farther from the group may catch the predator’s eye. Such cues may be at work when a white shark picks a young, vulnerable Cape fur seal out of the larger seal population at Seal Island.

The location and timing of predatory attacks are also far from indiscriminate. At high tide on the Farallon Islands, for instance, there is heavy competition for space where northern elephant seals can haul themselves onto the rocks, and the competition forces many low-ranking juve-nile seals into the water. Klimley—along with Peter Pyle and Scot D. Anderson, both wildlife biologists then at the Point Reyes Bird Observatory in California—has shown that at the Farallons, most white-shark attacks take place during high tide, near where the mammals enter and exit the water.

|

||

Similarly, at Seal Island, Cape fur seals leave for their foraging expeditions from a small rocky outcrop nicknamed the Launch Pad. Coordinated groups of between five and fifteen seals usually leave together, but they scatter while at sea and return alone or in small groups of two or three. White sharks attack almost any seal at Seal Island—juvenile or adult, male or female—but they particularly target lone, incoming, young-of-the-year seals close to the Launch Pad. The incoming seal pups have fewer compatriots with which to share predator-spotting duties than they do in the larger outgoing groups. Furthermore, they’re full and tired from foraging at sea, making them less likely to detect a stalking white shark.

The white shark relies on stealth and ambush when hunting seals. It stalks its prey from the obscurity of the depths, then attacks in a rush from below. Most attacks at Seal Island take place within two hours of sunrise, when the light is low. Then, the silhouette of a seal against the water’s surface is much easier to see from below than is the dark back of the shark against the watery gloom from above. The shark thus maximizes its visual advantage over its prey. The numbers confirm it: at dawn, white sharks at Seal Island enjoy a 55 percent predatory success rate. As the sun rises higher in the sky, light penetrates farther down into the water, and by late morning their success rate falls to about 40 percent. After that the sharks cease hunting actively, though some of them return to the hunt near sunset.

| ||

To avoid a shark attack, seals may leap in a zigzag pattern or even ride the pressure wave along a shark’s flank, safely away from its lethal jaws. If an attacking shark does not kill or incapacitate a seal in the initial strike, superior agility now favors the seal. The longer an attack continues, the less likely it will end in the shark’s favor. Cape fur seals never give up without a fight. Even when grasped between a white shark’s teeth, a Cape fur seal bites and claws its attacker. One has to admire their pluck against such a formidable predator.

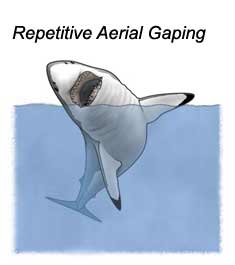

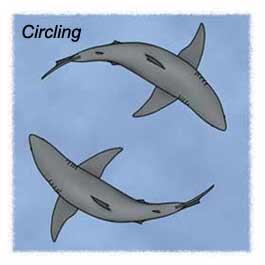

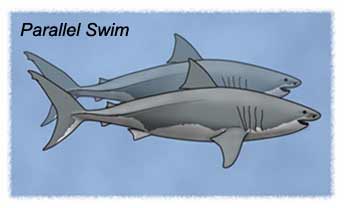

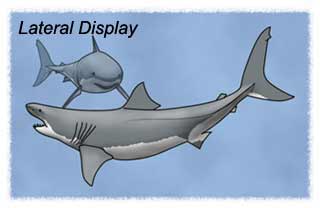

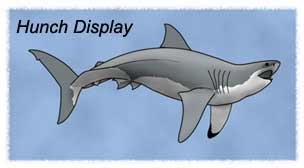

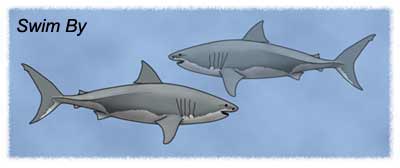

After the morning flush of predatory activity at Seal Island, white sharks turn to socializing. We have discovered, by observing both from the surface and with underwater cameras, that the social behavior of these sharks is astonishingly complex. During the past five years, we have cataloged twenty distinct social behaviors in white sharks at Seal Island, half of which are new to science. We are just beginning to understand their significance, but many are related to establishing social rank [see illustrations below].

|

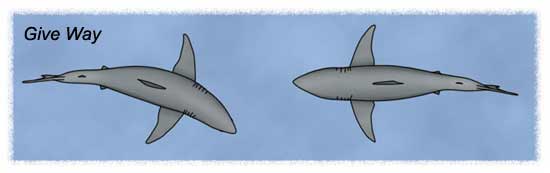

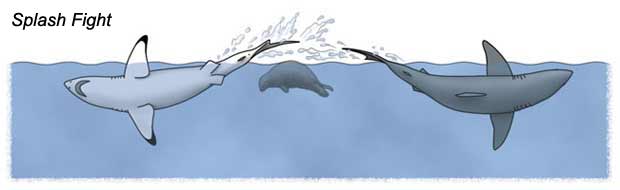

Rank appears to be based mainly on size, though squatter’s rights and sex also play a role. Large sharks dominate over smaller ones, established residents over newer arrivals, and females over males. Why such a focus on rank? The main reason is to avoid combat. As many as twenty-eight white sharks gather at Seal Island each day during the winter seal-hunting season, and competition among them for hunting sites and prey is intense. But since white sharks are such powerful, heavily armed predators, physical combat is a risky prospect. Indeed, unrestrained combat is extremely rare. Instead, the white sharks at Seal Island reduce competition by spacing themselves while hunting, and they resolve or avert conflicts through ritual and display.

| ||

For example, as was the case with Sneaky and Couz, two white sharks often swim side by side, possibly to compare their relative sizes; they may also parade past each other in opposite directions or follow each other in a circle. One shark may direct splashes at another by thrashing its tail, or it may leap out of the water in the other’s presence and crash to the surface. Once rank is established, the subordinate shark acts submissively toward the dominant shark—giving way if they meet, or avoiding a meeting altogether. And rank has its perks, which can include rights to a lower-ranking shark’s kill.

Another form of nonviolent, tension-diffusing behavior often takes place after a shark repeatedly fails to catch bait (typically a tuna head) or a rubber seal decoy: the shark holds its head above the surface while rhythmically opening and closing its jaws. In 1996 Wesley R. Strong, a shark investigator then affiliated with the Cousteau Society in Hampton, Virginia, suggested the behavior might be a socially nonprovocative way to vent frustration—the equivalent of a person punching a wall.

|

||

Complex social behaviors and predatory strategies imply intelligence. White sharks can certainly learn. The average shark at Seal Island catches its seal on 47 percent of its attempts. Older white sharks, however, hunt farther from the Launch Pad and enjoy much higher success rates than youngsters do. Certain white sharks at Seal Island that employ predatory tactics all their own catch their seals nearly 80 percent of the time. For example, most white sharks give up if a seal escapes, but a large female we call Rasta (for her extremely mellow disposition toward people and boats) is a relentless pursuer, and she can precisely anticipate a seal’s movements. She almost always claims her mark, and seems to have honed her hunting skills to a sharp edge through trial-and-error learning.

We are also learning that white sharks are highly curious creatures that systematically escalate their explorations from the visual to the tactile. Typically, they nip and nibble to investigate with their teeth and gums, which are remarkably dexterous and much more sensitive than their skin. Intriguingly, highly scarred individuals are always fearless when they make “tactile explorations” of our vessel, lines, and cages. By contrast, unscarred sharks are uniformly timid in their investigations. Some white sharks are so skittish that they flinch and veer away when they notice the smallest change in their environment. When such sharks resume their investigations, they do so from a greater distance. In fact, over the years we have observed remarkable consistency in the personalities of individual sharks. In addition to hunting style and degree of timidity, sharks are also consistent in such traits as their angle and direction of approach to an object of interest.

| ||

Klimley suggests that, compared with blubbery marine mammals, people are simply too muscular to constitute a worthwhile meal. Our view is different: we believe that white sharks probably bite people not to eat them but to satisfy their curiosity. Fortunately, the shark’s investigation of a person is usually interrupted by the victim’s brave companions.

For all the fear white sharks inspire, it is ironic that people probably pose the single greatest threat to white sharks. People kill them for sport and trophies, and hunt them to reduce their populations near swimming and surfing beaches. In addition, there’s a flourishing and lucrative black market in white-shark jaws, teeth, and fins, even though such trade is illegal under international law. White sharks take between nine and sixteen years to reach maturity, and females give birth to just two to ten pups every two or three years. Such a life in the slow lane makes the white shark extremely vulnerable to even moderate levels of fishing.

|

||

As September approaches, the white sharks’ hunting season at Seal Island draws to a close. Soon most of them will depart, remaining abroad until their return next May. The Cape fur seal pups that have survived this long have become experienced in the deadly dance between predator and prey. They are bigger, stronger, wiser—and thus much harder to catch. The handful of white sharks that remain in False Bay year-round probably shift to feeding on fishes such as yellowtail tuna, bull rays, and smaller sharks. In effect, they seasonally switch feeding strategies from energy maximization to numbers maximization.

Next May we, too, will return. But fieldwork always has its surprises, and we cannot predict what the white sharks of Seal Island will have in store for us.

|

Copyright © Natural History Magazine, Inc., 2006