October 2000

What went wrong with the Scandinavian westward expansion?

By Thomas H. McGovern and Sophia Perdikaris

Early in the ninth century, adventurous Scandinavians migrated to the northern British Isles (the Shetlands and Orkneys), around Britain to the Hebrides and into the Irish Sea, and still farther west to the apparently uninhabited Faeroe Islands. By A.D. 874 Scandinavian settlers, no doubt accompanied by substantial contingents of native British Islanders, were colonizing Iceland, and in about 985, Iceland-born Erik “the Red” Thorvaldson began the settlement of Greenland, recruiting mostly other Icelanders to join him as colonists. At the turn of the millennium, as recounted in Icelandic sagas first written down 300 years later, Erik’s sons explored parts of the Canadian Arctic and the coasts of “Vinland”—probably Newfoundland and adjacent Labrador. Any doubts that the Scandinavians did indeed reach the New World were laid to rest during the 1960s, with the discovery and excavation of L’Anse aux Meadows, a site in Newfoundland that dates to about 1000.

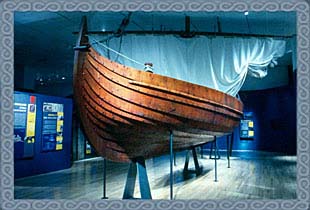

This westward expansion across the North Atlantic took nearly two centuries to complete, with each new colony, especially in its vulnerable early years, greatly dependent upon the preceding ones for settlers, livestock, and supplies. The enterprise hinged on the Scandinavians’ excellent ships and their skill in navigating across large bodies of water, a seafaring advantage that also enabled them to plunder European shores (in addition to their westward push, Scandinavians—including Norwegians, Swedes, Danes, and Finns—penetrated south as far as the Mediterranean and east as far as the Caspian Sea). As raiders they were known as the Vikings, a term that is now loosely applied to all Scandinavian peoples of the Viking Age (ca. 800-1100) and also, sometimes, of the Middle Ages (ca. 1100-1500). The impetus for migration came from overpopulation at home as well as from increased conflict between minor aristocrats, conflict that was fueled by the new, plundered wealth.

|

Where did these bright, ambitious, hard-working settlers go wrong? For an answer, we need to look beyond the Icelandic sagas and other written records—a precious but finite resource—and incorporate the testimony of pollen, soils, insect remains, human and animal bones, charcoal fragments, ice cores, and volcanic ash layers. The silent sagas contained in this archaeological, paleoenvironmental, and climatic evidence—assembled by many researchers during the past two decades-tell us that part of the problem may have been the settlers’ attempt to transplant a way of life that had worked in Scandinavia but ultimately proved unsuitable to the more marginal environments and less stable climates of Iceland, Greenland, and northern North America.

Animal bones and other materials collected from archaeological sites show that in their homelands, wealthy Scandinavians had large farmsteads with dairy cattle (also a source of meat), pigs, sheep and goats (exploited for wool or hair, as well as milk and meat), and horses (used for transport). The ideal farmstead had ample pastures, fields of barley—cultivated more to make beer than bread—and was located near sealing beaches, bird cliffs (providing meat, eggs, and eiderdown), and an inshore fishery that could be exploited year-round. Fishermen used hooks and long hand lines and usually carried out their trade from rocks or on boats that did not venture over the horizon. Archaeological finds in the Orkneys show that early Vikings successfully exported this comfortable lifestyle, based on an abundance of local resources.

At first, the settlers of southern Iceland replicated this pastoral ideal quite closely, but by the eleventh or early twelfth century, they, along with their pigs and goats, must have used up much of the forest. This may be the main reason that pigs, which need woodlands to thrive, drop out of the archaeological record at this time, as do goats, which probably were not as efficient as sheep at turning grass into milk. The relative numbers of cattle also decline in favor of sheep, probably because cows require better quality pasture. The old expectations and practices did not die so easily, however. When Erik the Red and his contemporaries settled Greenland, they sought to establish, wherever possible, not only the modified eleventh-century Icelandic farmstead but the original Scandinavian farmstead, rich in pigs and cattle. This simply did not work over the long term.

The vegetation of the North Atlantic, dominated by Old World plants all the way from Norway to western Greenland, probably gave the early settlers a false impression that the environment was uniform throughout the region. Viking farmers arriving in Iceland from northern Norway or the Shetlands would have been encouraged by the sight of pastures with sedges and grasses and dwarf woodlands of birch and willow resembling those at home. But the colonists from Scandinavia and the British Isles had crossed critical environmental thresholds when they went from islands warmed by the North Atlantic Drift (the northern extension of the Gulf Stream) to Iceland and Greenland, where these warm waters met cold currents from the north. The colder winters and shorter growing season made the green fields they encountered more fragile. While Scandinavian pastures and woods could sustain large concentrations of cattle and pigs, these same animals helped denude the landscapes of Iceland and Greenland within a few generations. In addition, the more variable climate was in a deceptively mild mood when the Vikings first arrived; subsequently, it not only fluctuated but followed an overall cooling trend that seems not to have reversed itself until the early twentieth century.

| Where did these bright, ambitious, hard-working settlers go wrong? |

The concealed environmental differences extended to the soils, which form at a far slower rate in both Iceland and Greenland because of the slower rate of plant growth and decomposition there. In Iceland the impact of Viking farmsteads on the land can be dated by analyzing layers of volcanic ash in soils, sediments, and ice caps. Rapid erosion occurred at many elevations after the initial settlement, probably as vegetation was consumed by livestock, turf stripped for house construction, and trees cut down for timber and fuel. Once compromised, the volcanic soil was vulnerable to wind erosion. The situation stabilized for a while, but between 1450 and 1750 additional waves of erosion started in the upland areas and moved downward.

The early Icelandic settlers apparently farmed a great deal of the island, since Viking Age archaeological sites are found at higher elevations and farther inland than any currently occupied farms. In 1998 Icelandic archaeologist Orri Vésteinsson discovered one such site, Sveigakot, in northern Iceland near Lake My’vatn, at the edge of what today, because of erosion, is a great desert of black sand and rock. Volcanic ash, carbon 14, and artifacts all date this site to the tenth century. Vésteinsson’s team has excavated substantial numbers of cattle, goat, and sheep bones and a generous collection of pig bones (which become very rare after 1000 in both Iceland and Greenland). Excavation also has turned up pieces of flattened birch bark (perhaps roof shingles) and large amounts of wood charcoal and iron smelting slag, all suggestive of forest resources long ago expended.

All in all, the early settlers—who probably anticipated that the climate would remain warm and that the grasses and trees would regrow at a rate comparable to that in Scandinavia—appear to have rapidly consumed what environmental historian William Cronon has called their “natural capital”—soils and vegetation that had built up over millennia. By the time they realized that soils and weather were less forgiving in the new land, severe and often irreversible damage had been done, and similar natural resources were lost to later generations. To compensate, the colonists turned increasingly to the sea.

Scandinavians had always hunted seabirds, seals, and occasionally whales, but preserved fish, especially cod and related species, was their main North Atlantic marine product. They used two principal methods of preservation. Stockfish consisted of fish that were beheaded, gutted, and air-dried at temperatures just around freezing, while for klippfish, the fish were beheaded, split open, and dried, sometimes—if the air was insufficiently cold—with salt.

Even before the ninth century, stockfish was produced in substantial amounts in northern Norway, especially around the cod spawning grounds off the Lofoten and Vesterålen Islands. Since the product had a shelf life of more than two years with no refrigeration, it was a resource that could be counted on even when the harvest failed or dairy supplies ran short. During the Viking Age, stockfish was traded to people in the south for barley and to the Saami reindeer herders in the north for furs. It could be taken along on boat voyages as a convenient, nutritious meal and was consumed on land in years when the harvest was poor or the sea uncooperative. In the hands of the Viking chieftains vying for royal authority, stockfish was not only a source of wealth but a means of ensuring status. When exchanged for barley, it permitted the brewing of the beer that made guests and dignitaries happy, secured alliances, and sanctified religious festivals.

Viking colonization of the North Atlantic may have contributed to the preserved fish trade. Sites in the Orkneys, Shetlands, and northern Scotland are particularly rich in cod and other deep-sea fishes. In Iceland preserved saltwater fish bones have been found on tenth-century inland sites such as Sveigakot. In Greenland, however, the principal marine food sources were seals and seabirds rather than fish, while walrus ivory and hide seem to have served as overseas trade goods.

| Most of the year-round and seasonal occupants of these new settlements were desperately poor, caught up in debt passed from one generation to the next. |

By 1100, at the end of the Viking Age, Norway had been unified under one king and the nation had been Christianized through its contact with Britain. Norwegian fisheries came under the direct control of the state and local bishops, and stockfish became a major source of royal and ecclesiastical revenue. Traded all over Europe, stockfish was no longer a subsistence foodstuff and item of barter, delivered personally by a fisherman to a local strongman, but an internationally exchanged commodity, a product of standardized size, value, and quality that could be bought and sold in distant countinghouses by men who would never see the fishermen or the fish. Archaeologically, this transformation can be discerned in the fish bones found at sites in Norway and Iceland: fewer fish species are represented (because of the concentration on cod fishing), and the estimated lengths for these fish fall mostly in the range suitable for stockfish (overly large fish would start to rot before they were fully preserved, while small fish would end up hard as rocks). Headless fish turn up on inland Norwegian and Icelandic sites dating to the Viking Age, but the numbers of such fish increase during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, especially in the new urban settlements that provided commercial markets for all sorts of commodities.

|

This second, commercial wave of European expansion did not reach Greenland before the colony met its end. Large-scale fishing seems to have developed in Iceland during the fourteenth century, but true fishing villages did not emerge there until full-scale commercialization of fishing was imposed in the eighteenth century by Denmark, which controlled the colony. Wherever commercialization penetrated, however, its effects were similar. It brought connections to a wider world, to manufactured goods, bread, beer, and brandy—but at the price of oppressive working conditions.

By the time Columbus set sail, Greenland was dead, Iceland was struggling to survive climate change and a drawn-down natural capital of soil and vegetation, and the northern isles of Britain had been captured by the Scottish crown. Industrial fishing was sending the northern Norwegians into debt—and into early graves—and Scandinavia was dominated by Danish elites, whose cultural aspirations were influenced by the free towns of northern Germany. The North Atlantic had become a very different place from the open frontier full of possibilities that Erik the Red and his contemporaries knew—in large part owing to the unintended consequences of choices made by the early Vikings themselves.

Archaeologists Thomas H. McGovern and Sophia Perdikaris have both done work on Scandinavian settlements in the North Atlantic—McGovern in the Shetland Islands, Iceland, and Greenland, and Perdikaris mainly in the Lofoten and Vesteralen island groups in northern Norway. McGovern is a professor of anthropology at Hunter College, of the City University of New York (CUNY), and coordinator of the North Atlantic Biocultural Organisation. Perdikaris is an assistant professor of anthropology and archaeology at CUNY’s Brooklyn College. She is also director of the Brooklyn College Zooarchaeology Laboratory and of CUNY’s Northern Science and Education Center.

Click here to visit the exhibition Web site for

Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga

Copyright © Natural History Magazine, Inc,