Natural History, December 1990

Columbus, My Enemy

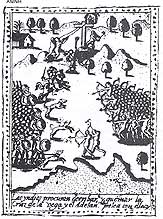

A Caribbean chief resists the first Spanish invaders.

By Samuel M. Wilson

|

![]() N May 1497, the Taíno ruler Guarionex was enmeshed in a potentially disastrous political situation. Five years had passed since the strange and dangerous Spaniards first appeared on the northeast shore of Hispaniola. For five years Guarionex had attempted to mediate between the foreigners and his people and to maintain his power and prestige among the other Taíno caciques, or chiefs, who were sometimes his confederates, sometimes his competitors, in the complex political terrain of the Greater Antilles.

N May 1497, the Taíno ruler Guarionex was enmeshed in a potentially disastrous political situation. Five years had passed since the strange and dangerous Spaniards first appeared on the northeast shore of Hispaniola. For five years Guarionex had attempted to mediate between the foreigners and his people and to maintain his power and prestige among the other Taíno caciques, or chiefs, who were sometimes his confederates, sometimes his competitors, in the complex political terrain of the Greater Antilles.

Two years earlier, Guarionex had witnessed the utter devastation the Spaniards could wreak in battle. Together with the other chiefs in La Vega Real—the largest, most fertile, and most densely populated valley on Hispaniola—he had set out to destroy the small force of Spaniards. Tens of thousands of Taíno, perhaps as many as one hundred thousand, had gathered from the largest chiefdoms on the island. They faced only about 200 Spaniards. But in battle the fury of the strangers had been awesome: twenty men with armored clothing had ridden through his people on enormous animals, inflicting horrible wounds with their lances and swords. Men on foot used terrifying weapons that exploded fire. The Europeans’ large dogs ran before them and with uncontrolled violence tore through the Taíno warriors. The Spaniards’ goal seemed to be not merely to impress or subdue the Taíno or to embarrass the chiefs into joining them as subordinates but to kill as many people as possible. Even after the battle they tortured to death some of the most respected chiefs in La Vega Real.

Soon afterward, however, the foreigners’ ferocity strangely abated. They gave the remaining chiefs remarkable presents—glass beads, copper bells, brightly colored clothes.

| Still, the Spaniards required more than tribute. Because the Spanish ships came so infrequently and brought so little food, the colonists constantly roamed the countryside demanding the hospitality of the Taíno villages. |

Still, the Spaniards required more than tribute. Because the Spanish ships came so infrequently and brought so little food, the colonists constantly roamed the countryside demanding the hospitality of the Taíno villages. Sometimes hundreds of Spaniards and the Indians that followed them would descend on a village for a few weeks. They called for food and seemed to eat much more than a Taíno would. And they did not eat just the food that was ready to be harvested; they also ate the manioc that normally would have stayed in the ground for another six months, and so after they left, famine followed.

By 1497, after two years of epidemics and famine following the arrival of the Spaniards, the other chiefs were pushing Guarionex to put up some resistance. Guarionex was a coward, they argued; groups of Spaniards who hated Columbus and his kin were living in Taíno villages and had promised to help the Taíno in battle if they would rise up again. The Spaniard Francisco de Roldán led a small army of dissatisfied Spaniards; he had told the chief Marque that he would help drive the Spaniards out of Concepción de la Vega, the fort that controlled the center of the island. Roldán promised that if the Taíno won, the Spaniards would stop demanding tribute. His offer was attractive to many of the chiefs in La Vega Real. Most of them were subordinate to Guarionex in the Taíno hierarchy of social and political status, but their opinions were extremely important.

The Taíno world stretched more than 1,000 miles from east to west. Beginning more than 2,000 years before the arrival of the Spaniards, the ancestors of the Taíno had moved into the Caribbean archipelago from the northeast coast of mainland South America. They spoke a language (called Taíno) of the Arawakan family, one of the most widely dispersed languages in South America. By A.D.700, after occupying the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico, they had pushed farther into the islands of the southern Bahamas and the western Greater Antilles—Hispaniola, Jamaica, and Cuba.

The ancestors of the Taíno were people of the tropical forest, who made their living by growing manioc and other root crops and by hunting, fishing, and collecting wild animals and plants. In the centuries of living in their new home, however, the Taíno way of life had become distinctively Caribbean. Ways of growing and collecting food had been adapted to island environments; social and political institutions had emerged that allowed a dense population to endure successfully in an island context. The sea served to unite, rather than separate, the Taíno. The elaborate oceangoing canoes of the chiefs could hold as many as 100 people, and voyages between islands were routine.

In addition to intermarriage between high-ranking lineages, the large chiefdoms of Hispaniola and the other Greater Antilles interacted with one another through a ball game. As in Mesoamerica and parts of South America, the Taíno played the game on large, flat courts lined with stones or earthen embankments. The game was played with a gum rubber ball, which could not be caught or struck by a player’s hands or feet. For the Taíno, the game was much more than sport: it was a focus for religious festivals, feasting, trade, intermarriage, and the (relatively) peaceful resolution of conflicts.

Since the ancestors of the Taíno had moved onto the islands of the western Greater Antilles, the chiefdoms had been growing larger and more powerful. In 1492 Guarionex was one

| Among the Taíno, a chief’s position was vulnerable: he could be deposed by his brothers or nephews or even by a member of another lineage. |

Among the Taíno, a chief’s power was measured by his ability to convince others that his authority sprang from his birth into a maternal lineage of high status, his special relationship with supernatural spirits, and his political acumen. But his position was vulnerable; he could be deposed by his brothers or nephews or even by a member of another lineage. This, Guarionex greatly feared. Despite misgivings that the rout of two years earlier would be repeated, he lent his support to the planned uprising.

Even as Guarionex was being pushed into battle by his confederates, Don Bartolomé Colón, Columbus’s brother, learned of the impending uprising in La Vega Real. He had heard of Roldán’s plan to join with the Taíno to take over the fort at Concepción de la Vega. If Roldán succeeded, the pro-Columbus faction would be cut in half—part would be in the coastal colony of Isabela and other forts in the north, part in newly founded Santo Domingo and other settlements in the south. Moving quickly with the 300 Spaniards he had with him, Bartolomé came into La Vega Real from the south. His men reinforced the fort, but they were still vastly outmatched by the surrounding Guarionex-Roldán alliance.

In many ways Bartolomé was the more capable of the Columbus brothers. He was described by Bartolomé de las Casas, an important chronicler of the early contact period in the New World, as “a man who was prudent and very brave, more calculating and astute than he appeared, and without the simplicity of Christopher. He had a Latin bearing, and was expert in all of the things of men. . . . He was taller than average in body, had a commanding and honorable appearance, although not as much so as the Admiral.”

As long as the Columbus family was the dominant Spanish faction of Hispaniola, Bartolomé was its de facto leader. He alienated members of rival factions to a lesser extent than his brother and interacted more effectively with the Taíno elite. In the two years since the first uprising in La Vega Real, he had learned to speak some Taíno and had developed relationships with many of the chiefs, including Guarionex. He knew that the Indian leaders were becoming desperate.

As Bartolomé moved into La Vega Real, Guarionex and his confederates were assembling and preparing for battle. The allied chiefs were scattered in several villages within the central valley. The situation was different from two years earlier, when the Spaniards had so overawed the Taíno that no man could stand before them. Now the Taíno understood the power of the swords and horses, and the firearms had lost some of their terror. Moreover, they truly felt that they had no other hope but to defeat the Spaniards.

|

| In a breach of Taíno battle etiquette that was devastatingly effective for its novelty, Bartolomé staged a midnight raid on the surrounding villages. |

In a breach of Taíno battle etiquette that was devastatingly effective for its novelty, Bartolomé staged a midnight raid on the surrounding villages. His plan was to capture many of the chiefs before they could attack in the morning. Small groups of horses rode into the villages and carried off fourteen chiefs before any defense could be organized. Bartolomé himself went into the large village of Guarionex and took the chief back to the fort. Las Casas wrote that “they killed many of the captured leaders, from those who appeared to have been the instigators, not with any other punishment (I have no doubt) except by burning them alive, for this is what was commonly done.”

The raid threw the Taíno into chaos. Without their chiefs they were doubly lost. Their leaders not only directed warriors in battle but also mediated between the Taíno and supernatural spirit-helpers, who could bring them success. In the morning, according to Las Casas’s account:

“Five thousand men arrived, all without weapons, wailing and very upset, crying bitter tears, begging that they be given their king Guarionex and their other leaders, fearing that the caciques would be killed or burned alive. Don Bartolomé, having compassion for them and seeing their piety for their natural leaders, and knowing the innate goodness of Guarionex, who was more inclined to put up with and suffer with tolerance the aggravations and injuries done by the Christians, rather than think of or take vengeance, gave them their king and other leaders.”

Compassion it may have been, but Bartolomé and his men were still in the middle of thousands of desperate people, and Roldán was still waiting in the wings. Bartolomé knew that without the political organization the chiefs provided, the tribute system would quickly collapse. Fate had cast Bartolomé and Guarionex as strange allies, each dependent on the other for his authority and survival.

This partnership, however, was fragile. Famine and disease were unabated in the villages, and among the Taíno the feeling of despair continued to grow. Guarionex was unable to protect his people from either the tribute demands of Columbus and the Crown or the unofficial demands for food and gold made by the anti-Columbus faction of Spaniards. Increasingly, Guarionex was viewed as a tool of the Columbus family, and his support from the other chiefs, from the pro-Roldán faction, and from his own people began to evaporate. He was able to maintain his position as a powerful chief for little more than a year after the fourteen chiefs had been captured, but then had to flee La Vega Real with his family.

Even then Guarionex could not find safety, because Bartolomé, fearing that Guarionex would return with an army, hunted him down in the mountains of northern Hispaniola, where he had sought refuge. Guarionex and his people had been hidden by Mayobanex, the most powerful chief in the northern mountains and perhaps a distant kinsman of Guarionex’s. Bartolomé’s capture of Guarionex brought about the destruction of this chiefdom as well, by the same strategy used elsewhere—capture the chiefs as hostages to be ransomed (but not released) in exchange for their peoples’ tribute payments. Guarionex was held in chains at Concepción until 1502, when he was sent to Spain. His ship sank in a storm, and he died along with all the ship’s crew.

The same forces that combined to bring Guarionex’s rule to an end in La Vega Real were acting on all the other chiefdoms on Hispaniola and, ultimately, on others throughout the Greater Antilles. By 1500, most of the large political structures that existed on Hispaniola in 1492 had collapsed. For the Taíno, political disintegration and the decimation of the population occurred simultaneously.

The impact of the Europeans’ arrival was felt differently on other islands of the Caribbean, just as it was in different parts of the New World. Ponce de León’s conquest of Puerto Rico began in the early 1500s and quickly brought about the destruction of the Taíno way of life there. On Cuba the first Spanish attempt at colonization was less intense, in part because no gold was found, and in part because the discovery and conquest of Mexico diverted the attention of Spanish fortune seekers. Indian populations there were not completely destroyed. In the eastern Caribbean, the Carib Indians were largely bypassed by early colonizers. Their descendants survive today as the Garifuna of Central America, although their preconquest island culture has been transformed greatly through five centuries of interaction with Africans and Europeans.

The indigenous societies of North, Central, and South America survived the arrival of Europeans with different degrees of success in what we have come to view as the remote “contact period.” Five hundred years, however, is a short fragment of human history. We are still negotiating the coexistence and synthesis of peoples with African, European, Asian, and Native American ancestries and heritages. Guarionex’s struggle to retain his political status, to navigate the treacherous early years of the Spanish conquest, and ultimately to save his own life is just one story in this continuing process.

Copyright © Natural History Magazine, Inc.