Natural History, June 1988

The Halloween Mask Episode

A gull researcher learns the barefaced truth about western gulls.

![]()

N an otherwise ordinary day in the middle of the 1980 breeding season, the western gulls on Southeast Farallon Island suddenly went berserk. Just moments earlier, many of the 25,000 birds in this colony had been calmly incubating their eggs. But the moment I stepped through the doorway of the old Coast Guard house that serves as the living quarters for biologists working on the island, a full third of the gull population rose up and circled around in a panic, giving strident distress calls. It was as if a bomb had exploded, but the sad truth was that I had alarmed the gulls. Normally, incubating Farallon gulls aren’t bothered by people working on the island. Even gulls nesting on the border of much-used trails remain calm as people pass by. The gulls’ extraordinary reaction on this particular day was the culmination of a series of inroads I had made on their security.

N an otherwise ordinary day in the middle of the 1980 breeding season, the western gulls on Southeast Farallon Island suddenly went berserk. Just moments earlier, many of the 25,000 birds in this colony had been calmly incubating their eggs. But the moment I stepped through the doorway of the old Coast Guard house that serves as the living quarters for biologists working on the island, a full third of the gull population rose up and circled around in a panic, giving strident distress calls. It was as if a bomb had exploded, but the sad truth was that I had alarmed the gulls. Normally, incubating Farallon gulls aren’t bothered by people working on the island. Even gulls nesting on the border of much-used trails remain calm as people pass by. The gulls’ extraordinary reaction on this particular day was the culmination of a series of inroads I had made on their security.

Southeast Farallon Island, the largest of five islands thirty miles west of San Francisco, is the breeding site of twelve species of seabirds, including western gulls, common murres, pigeon guillemots, tufted puffins, black oystercatchers, three species of cormorant, two of auklets, and two of storm petrels. The Farallon seabird rookery is the largest in the lower forty-eight states, with a breeding population of about a quarter million birds.

During the early nineteenth century, however, the Farallon seabird population was well over a half million, perhaps even a million birds; the most numerous were common murres. This changed with the coming of Europeans, whose depradations on Farallon avifauna peaked in the mid-to-late 1800s, when an estimated 14 million eggs were harvested and sold. As the eggers drove the murres from their nests, predatory western gulls were quick to take advantage of the situation, often eating many murre eggs before the eggers could collect them. To get rid of their avian competitors, eggers began crushing the gull eggs on sight, thereby reducing the gull population.

Disturbance by humans affected other seabirds as well: by the beginning of this century only about 100,000 birds bred on the Farallons. So few murres (60,000) were left that egging practices, no long profitable, were ended. Meanwhile, Southeast Farallon had been manned by lighthouse keepers, whose dogs, cats, and other domestic animals prevented the gulls from breeding anywhere except the most inaccessible places. As a result, the gull population continued to decline; by 1903, only a few thousand were breeding on the island.

In 1972 Farallon birds were given full protection. By 1979, the gull population had risen to 25,000. Now they nest all over the island—in extensive areas once inhabited by fur seals before they were extirpated by Russian and New England sealers in the nineteenth century—and their numbers seem to be slowly rising.

Point Reyes biologists and volunteers have banded 2,000 western gull chicks on the island each year since 1971. Each chick receives a metal U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service band on one leg and one or more colored, plastic bands on the other. A different color or leg combination has been used each year. Western gulls reach adulthood in four years, and immature gulls spend their growing-up years along the coast of the mainland, from Washington to Mexico. The first group of banded birds returned to breed in 1975, and the number of banded birds breeding on the island has been steadily increasing ever since.

I was using this valuable resource—a population of known individuals of known ages—to study whether survivorship and breeding success were age related, how adult gulls became breeders, and where and how their young dispersed. This required surveillance of many of the known-age individuals, a task I accomplished by reading the numbers on their bands with a spotting scope. Since this was my only means of recognizing individual birds, I was alarmed to discover in 1978 that they were losing their aluminum bands at a high rate (later determined to be about 16 percent per year). I therefore began rebanding birds with stainless steel.

Rebanding an adult gull is a much different proposition from banding a flightless, downy chick trying to hide in a rock crevice. To trap each grown bird, I placed a cord noose around the rim of its nest and

Although my activities appeared to be causing a major disturbance in the colony, I was relieved that few gulls used the occasion to steal eggs from the nests of other gulls. |

Although my activities appeared to be causing a major disturbance in the colony, I was relieved that few gulls used the occasion to steal eggs from the nests of other gulls, as they sometimes do even under more usual conditions. Apparently they were concentrating on me as a predator and were too distracted to consider egg stealing. Besides calling and flying about in circles, they swooped closely over my head, sometimes knocking my hat off. Once, presumably through miscalculation, a gull struck the back of my head. In addition, airborne gulls frequently bombarded me with excrement. For these reasons, and to reduce disturbance in the colony, I slipped snared birds into a canvas “gull bag” as quickly as possible. Once the victim was in the bag, the other gulls calmed immediately and landed at their nest sites. After weighing and rebanding the gull, I took it out of the bag for release; at that instant there was another, less intense distress response from the gulls nesting nearby.

During the rebanding project, I found that the gulls’ distress response intensified as the season progressed and more birds were trapped. If I noosed only one or two gulls every few days, usually at different locations on the island, agitation in the colony remained low. In 1980, however, I arrived late in the incubation period and had a very short time in which to reband a number of older, known-age birds of great value to my research. After I had trapped nine birds in two days, the intensity of responses escalated well beyond my expectations: the colony was in an uproar at the sight of me leaving the house. Obviously the birds were recognizing me. Perhaps what I needed was disguise.

|

My dilemma naturally became the talk of the household, and in conferring with my co- worker Bob Boekelheide, we came up with a possible remedy. Other humans on the island generated no distress reaction from the gulls. Obviously the birds were recognizing me. Perhaps what I needed was a disguise.

| Other humans on the island generated no distress reaction from the gulls. Obviously the birds were recognizing me. Perhaps what I needed was disguise. |

While I outfitted myself, Bob and I pondered the western gulls’ apparent ability to pick out one “enemy” among several humans, an interesting find in itself. We knew from studies conducted by others that birds can discern species that prey on them, but to my knowledge the capacity to remember individual predators hadn’t been demonstrated. In cases where certain individuals of a given species are predators and others are not, this kind of recognition, requiring a well-developed memory, might be a real advantage.

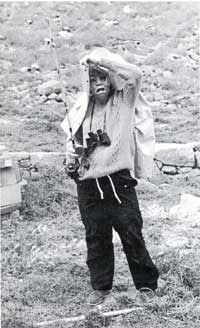

But just how do western gulls recognize different human beings? The conditions I had inadvertently created gave us an unusual chance to investigate. I began by thoroughly concealing my identity. I wore a wide-brimmed straw hat instead of my yellow stocking cap, clothes that didn’t fit well and that I had never worn before, and a Halloween mask with a bright green face and orange hair. I left the house in the this garb and walked with a pronounced limp down the main path through the gull colony. To my astonishment, absolute calm prevailed. I found myself eye to eye with individual gulls I hadn’t seen for quite a while.

Although we had made some progress, we were still asking the same question, that is, which part or parts of my disguise prevented the gulls from recognizing me? Besides an exciting opportunity to gain a better understanding of gulls’ perceptions of humans, I was soberly asking myself a more mundane, but practical question, “Do I have to wear this costume for the duration of my stay on the island?” I changed into my regular clothes, kept the green-and-orange mask and straw hat, went back outdoors, and walked down the main path without a limp. The gulls remained calm. For the next stage of the experiment, I wore my yellow stocking cap (a different color from the other head gear then being worn on the island) but retained the mask. When I walked through the colony, a mild distress response ensued, so I went back indoors once again and replaced the yellow cap with a gray one. This time the gulls remained calm as I passed by.

| The instant I appeared outside, the gulls flew

up in mass distress—an obvious response to my familiar face! |

At this point, the only part of the original disguise that remained unchanged was the Halloween mask. To test our suspicions that the gulls were basing their recognition on my facial features, I put the poorly fitting clothes back on, along with the straw hat, but I took off the mask. The instant I appeared outside, the gulls flew up in mass distress—an obvious response to my familiar face!

These results seemed amazing at first, but why shouldn’t western gulls use the same methods we do to recognize individuals? Biologist Niko Tinbergen has noted that, like humans, gulls have an excellent ability to distinguish among forms. Both species’ sensory mechanisms are primarily audio-visual and are similarly keen. Taking this a step further, these powers of recognition work to the advantage of gulls living in a large colony. For example, we know from Tinbergen’s work that nesting gulls can recognize their mates in flight at a distance of one hundred feet, and that they also recognize neighbors by sight. Well-developed recognition between mates is important because the pair must prevent other gulls from landing in their territories and stealing eggs or young. Recognition of neighbors is also important because some members of the colony specialize in pirating food or plundering nests. We don’t know what cues are used, but as Tinbergen suggested, facial features may well be important—especially since the shape of a gull’s head is determined largely by bony structures that vary considerably, whereas body areas are more densely feathered and, at least to the human eye, are less individualized.

|

All things considered, the Halloween mask episode of 1980 certainly added a new dimension to my respect for these birds. Even at the beginning of the 1981 breeding season, when I appeared on the island barefaced, many gulls flew up and objected to my presence, remembering my face a full year later. My own ability to identify gulls by reading their band numbers seemed crude in comparison.