Pick from the Past

Natural History, November 1957

![]()

|

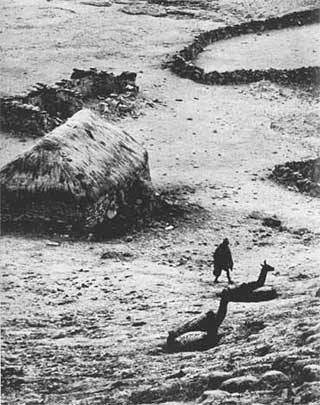

In this barren part of Peru, people still use the

Inca system of keeping records, the quipu.

By John Cohen

Mr. Cohen, who holds a Master’s degree in Fine Arts

from Yale, made these fine photographs during a seven-

month stay in Peru, studying Indian textile techniques.

![]()

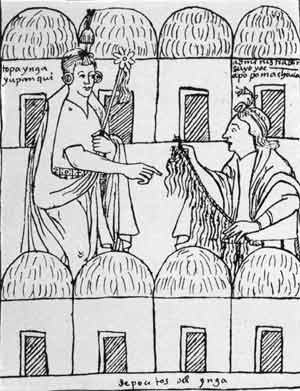

OVER four hundred years ago, during the time of the Inca Empire, the people of Peru had developed a system for keeping various accounts without the use of writing. They tied knots in cords in special ways, thereby establishing a numerical record. These knotted cords, known as "quipus," have been discovered in a number of ancient Peruvian graves.

Both the cords and their interpreters were inadequately described by Spanish chroniclers at the time of the conquest, and the exact kind of record which the Peruvians kept by means of their quipus has never been clearly established. Some quipus may have indicated dates, but the terms used—lunar months, solar years or other cycles—remain unknown. Almost certainly, others were routine inventories—so many baskets of potatoes, so many llamas, so many ponchos or pots or gold ornaments—but, again, the commodities concerned cannot now be determined.

One needs only to examine these ancient quipus, with their complex use of a variety of colored yarns, to come to the conclusion that the quipu-keepers occupied a special position in past Peruvian society. But, soon after the Conquest, the practice of quipu-keeping—and perhaps the men who understood the art—were no longer to be found.

| ||

It was thus with some sense of rediscovering the past that, in March, 1957, I arrived at a remote Quechua community in Peru where use of the quipu still survived.

The region of Q’eros lies between six and sixteen thousand feet above sea level, on the eastern slope of the Andes in southern Peru, some 100 miles from the ancient Inca capital, Cuzco. Eastward from Q’eros, the jungle of the montaña begins: westward, the Andes rise to their snow-capped pinnacles, 17,000 feet and higher. The area is isolated, both geographically and culturally. Only recently have roads been built from west to east through this section of the mountains, and none of the new roads comes within miles of the Q’eros area.

Although the communities of the region have churches, the traveling priests, who visit other isolated Indian communities, rarely come here. There are no schools for the children. Spanish is not spoken: the language is exclusively Quechua. The land is held by absentee haciendistas, but even their mayor domos seldom visit the isolated Q’eros communities.

Indeed, the only contacts with the outside world come from a few itinerant peddlers who cross the mountains from the west to barter buttons, pottery or dyestuffs for local alpaca wool, and, from the east, from trade with the primitive peoples of the montaña, from whom the Q’eros communities obtain the bright feathers of jungle birds and some of the large snail shells they use in their festivals.

Traveling in Peru to study contemporary weaving-techniques, I first heard of Q’eros in connection with two rumors—that these isolated people reputedly "wove from the left" and that they "kept quipus." Evidence of the survival of quipus in another remote community had already been reported by the Peruvian ethnologist, Nuñez del Prado, although I was not aware of this at the time. Since textiles were my prime interest, the first of these two rumors appeared worthy of pursuit (later, it proved baseless). So I set out for Q’eros.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To reach the area meant nearly a day’s ride in a truck along the one-way mountain roads eastward from Cuzco. Then, when the road could bring me no closer, I went on by horse through the 16,000-foot divide beyond which the Q’eros region lies. On my arrival, I found a society so isolated that it was not difficult to imagine I had returned through the centuries to the time of the Incas.

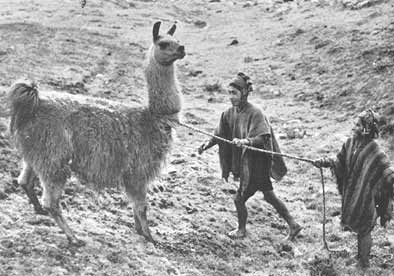

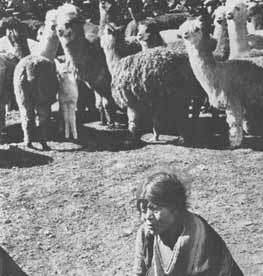

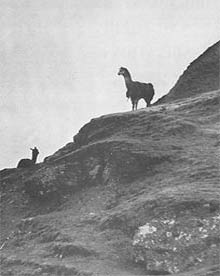

Although the people of Q’eros choose to live at high altitudes, they utilize the full range of their mountain slope. In the warmer, low regions, they cultivate corn. Higher up, where flat land cannot be found, they plant potatoes. Finally, in the barren pastures just below snowline, at altitudes ranging from 14,000 to 16,000 feet, they keep their flocks of llamas and alpacas—their beasts of burden and their source of wool for weaving, their dung for fuel at these treeless heights, and an occasional feast of meat.

|

Because the Q’cros people do not own the land on which they dwell, each adult male member of the community must work half the year for his absentee haciendista. This debt is paid by cultivating half the cornfields for the haciendista’s benefit, and by tending the haciendista’s half of the communities’ herds.

Why do the people of Q’eros choose to live just below the snow line, in harsh and desolate terrain, when richer land and warmer climate are at hand below them on the mountain slope? To this question, the people offered me a number of answers. The llamas and alpacas, they said, prefer the mountain tops and, indeed, these animals seem to do better at higher altitudes. In the lower regions, they added, their flocks are in greater danger of attack by pumas. The last word I had on this subject was from a young girl of Q’eros: it was well known, she said, that people who lived down by the jungle soon had their teeth go bad! Whatever the underlying cause, the Q’eros people—as do most Andean Indians—fit their high environment. Their chests are larger and their red blood cell count is higher than normal: both adaptations help them handle the oxygen-poor air efficiently. Like other Andean Indians, they also chew coca leaves. At an altitude where any exertion brought my own pulse-rate from a normal 70-per-minute to as high as 160, they led normal lives.

Soon after my arrival in Q’eros with the rumor about “weaving from the left” amply deflated, I decided to run down the second rumor, by seeking the keeper of the quipus. Using the equivalent word in Spanish, “contador,” I was met with blank stares until I had first described a quipu in detail and then delivered a brief lecture on its presumed function. I was then told that “the Quipu” (as the keeper is himself called in Q’eros ) was away with his flocks and would not return until nightfall.

In fact, it was three more days before I was able to talk to the Quipu of Q’eros. In this isolated community, it was his responsibility to keep count of the livestock, and the mayor domo had sent word that he wished an immediate report.

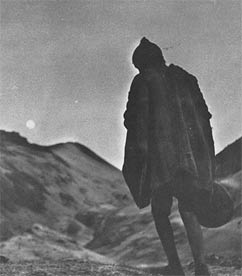

At the very time that I asked after him, the Quipu was at work in the corrals, knotting cords of various textures and colors in a census of the Q’eros flocks. Early next morning, with his carefully prepared record tucked in a bundle, with some dry corn and potatoes for nourishment and a little coca for comfort,

|

The next day, I talked with the Quipu—a man whose ancient art was so little known that even his wife was unable to point out for me which were the quipus and which merely miscerllaneous aggregations of string in her husband’s bundle. No, he replied to my question, none of his quipus was for sale. But, yes, he would be glad to make me one, as an example.

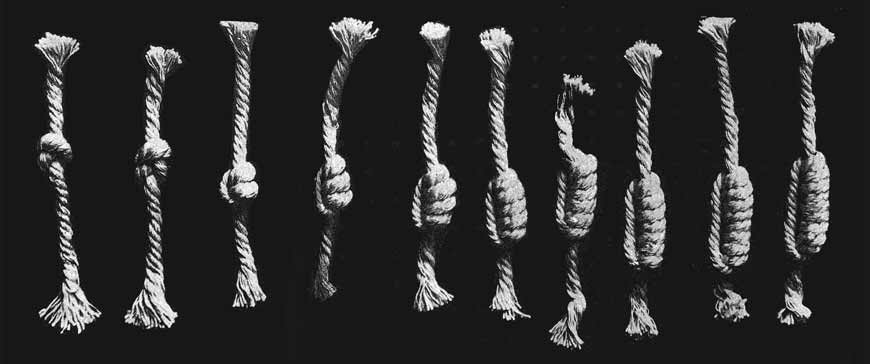

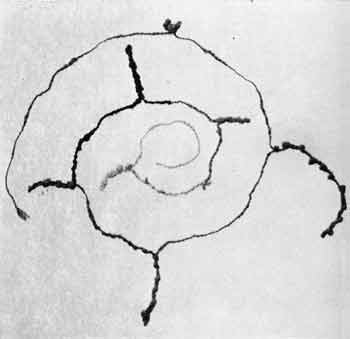

With the various strands of colored wool in his bundle, he began work—naming the numbers of the knots as he did so. Seven little knots for seven units of one; four medium knots for units of ten; two large knots for hundreds: before my eyes, the Quipu had produced understandable, decimal “247.”

As he explained, a series of such knots on a strand of a different color could represent another category—female, as opposed to male llamas, for example. Thus, a bundle of differently knotted and colored cords could represent the count, by categories, of all the community’s flocks. Such had been the quipu he carried across the mountains to the graceless mayor domo.

| ||

Was there any tradition as to the choice of colors for different categories? The Quipu of Q’eros said “no.” Anything that came to hand would do for a quipu, a scrap of wool, a bit of twine, even plant fibre, roughly twisted into string. Perhaps there had been a mastercode once, but—if so—I saw that no clue to it remained with the Quipu of Q’eros. So far as he was concerned, colors were selected at random and designated only for the specific occasion.

Thus quipu, as it survives at Q’eros today, is an extremely simple device. The knots no longer follow the complex ancient variations from one to nine; size, rather than position, is the clue to higher numeral values. Perhaps its simplicity and its continued usefulness is the secret of this quipu’d survival.

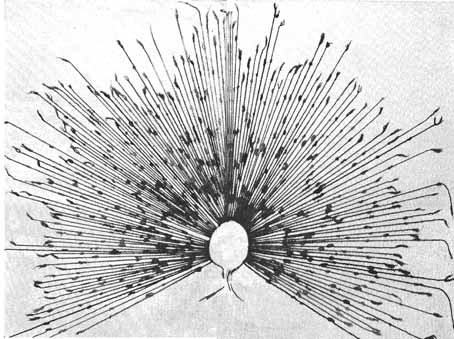

Compare a contemporary Q’eros quipu with one found in a burial of Inca times (see photographs). In basic form, one resembles the other: but the ancient quipu is sophisticated; the modern one, crude. This distinction was perhaps as true of Q’eros and its people at the peak of the Andes’ pre-Columbian civilization as it is today. At Q’eros, what we may see is a remnant of Sierra Indians who were as much bypassed by the highly organized society of the Inca Empire as they are bypassed by the Hispanic Peru of today. In such a harsh environment, where energies must be mainly devoted to staying alive, there is little impulse to keep up with the world.

| |||||||||||||