| Pick from the Past Natural History, February 1948 |

The Watch

| ||

The following article was brought to the attention |

|

|

![]()

IN 1931, when I was planning to visit the island of Hiva Oa in the Marquesas Group, I was told that on going ashore to the palm tree beach, I might be stopped by a short, white-haired native with a kindly face who would try to sell me a watch. “Don’t just shake your head and hurry on,” I was advised. “If you do, you will miss a remarkable story.”

It happened almost exactly as predicted. The barefooted man in the white drill suit was Samuel Kekela; and his wife was with him. Samuel Kekela was the son of James Kekela, the founder of the largest mission station at Puamau, Hiva Oa. When the elder Kekela died, his son Samuel inherited this large gold watch, which had been sent to his father in 1864 by none other than Abraham Lincoln. The watch was an expression of Lincoln’s thanks to Kekela for his part in saving the life of an American seaman who was about to be eaten by cannibals at Puamau.

It happened in this way. The wild cannibal tribes of Puamau had long nursed a hatred for the white sailors, a thirst for vengeance which had started when a Peruvian whaling ship sailed into the bay, firing upon the defenseless villages, ravishing the native girls, and carrying off men to work in the mines of Peru. The Puamau tribes took a pledge then and there to eat the next white sailor found ashore.

One day the first mate of an American whaler, having heard of the astonishing beauty of the native girls, came ashore in Puamau. With promises of a prize beauty of their tribe, the bland-faced native men enticed the unsuspecting sailor farther up the valley, away from the mission station.

|

James Kekela had been away from Puamau when the ship arrived. According to his own account, when he returned many people told him, “A certain white man is about to be roasted.”

“Who is doing it?” Kekela asked.

He was informed that the leader was a chief named Mato, whose son had been kidnaped by Spanish seamen.

Kekela secured additional information from his Hawaiian associate, Rev. Alexander Kaukau, who had tried to dissuade the chief from killing the white man. But Mato, recalling the kidnaping of his son, only answered, “They are all one kind, white men. This is all I have to say to you, Kaukau, whether the captain gives me a new boat or not, I shall roast this white man.”

But this did not discourage Kekela. He sent an emissary to Mato offering his own boat and anything else the chief wanted in exchange for the life of the sailor. Then, the next morning, he dressed himself in his Sunday clothes and, accompanied by Kaukau, rushed up the valley with only the Bible in his hand. When they arrived, Mato and his men were ready to start cooking the white man. Kekela strode past the glowering natives, knelt over the terrified victim, and prayed for him. He then met with Mato and talked with him. The chief of the cannibals was no doubt impressed with Kekela’s composure and sartorial distinction. Some sort of transaction appeared possible. At this point, another friend of Kekela’s stepped forward with a gun and offered it to the chief. This gesture, added to the impression Kekela had already made and the gifts he had promised, convinced the chief, and Jonathan Whalon was spared. Kekela at once led him to his house where the seaman would be safe from the young warriors, should they attempt to recapture him.

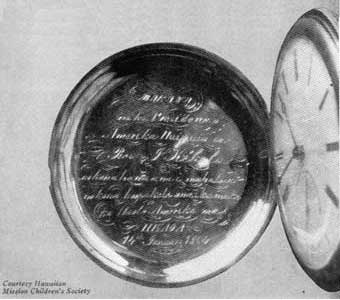

The dramatic circumstances of Jonathan Whalon’s capture and rescue were reported when his ship reached America, and the incident eventually came to the attention of President Abraham Lincoln. Al though the President was engrossed in the war between the States, he was so moved that he sent $500 in gold to Dr. McBride, U.S. Minister resident in Honolulu, for the purchase of suitable gifts that would express his gratitude to those who had participated in the rescue. Most interesting among these gifts is the large gold watch that is shown here, and it is still in existence. The inscription on it is translated from Hawaiian as follows:

From the

President of the United States

to

Rev. J. Kekela

For His Noble Conduct in Rescuing

An American Citizen from Death

On the Island of Hiva Oa

Januray 14, 1864

A similar watch is said to have been given to Kaukau, Kekela’s associate in the rescue, but the writer does not know its whereabouts. Various other presents were given, but they also seem to have become scattered during the many years that have passed since the occurrence of this interesting but little-known event.

Kekela acknowledged receipt of his gift in a personal letter to the President of the United States. “We have received your gifts of friendship,” he wrote. “. . . Ah! I greatly honor your interest in this countryman of yours. It is, indeed, in keeping with all I have known of your acts as President of the United States . . .” Kekela signed the letter: “I am, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, your ob’t. serv’t., James Kekela.”

|

When Robert Louis Stevenson, who was not without bias against Protestant missionary efforts in the South Seas, saw this letter, he was moved to say, “I do not envy the man who can read it without emotion.”

I first saw this watch in 1981, during a visit to the Marquesas, when it was offered to me for purchase. I saw it again in 1983 at Hiva Oa, when a friend of Kekela’s attempted to sell it aboard the schooner I was on; he explained that Kekela was in bed with rheumatism. The watchcase was marred a little where, as Kekela had explained to me, his father had banged it vehemently on the pulpit as he exhorted his cannibal parishioners to change their diet from puaka enata (“long-pig”) to just plain pig.

I was often sorry that I had not been able to buy the watch. Surely I could have placed it in the hands of some wealthy collector of old and famous timepieces. But now it has found its proper home. It has become the property of the Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society in Honolulu; and when the dream of a historical museum for Honolulu materializes, it is hoped that this historic treasure will be placed there on permanent exhibition.

Many changes have come to the Islands since the elder Kekela hammered the pulpit with his famous watch. But for those who would otherwise forget what the Islands were like less than a century ago, James Kekela’s memorial tablet bears this inscription as a reminder: “. . . in 1864 he was signally rewarded by Abraham Lincoln for rescuing an American seaman from cannibals.”

|

Postscript by Prentice Alexander I happened upon the story quite by accident, while doing genealogy, and trying to write a little family history for my grandchildren. All or most of this information was gathered from the New Bedford Public Library, the Kendall Whaling Institute, and the National Archives. Jonathan Whalon was born at Dartmouth, Massachusetts, in 1822, and died at Westport, Massachusetts, April 18, 1873. On July 13, 1841, he applied for and was granted Seaman’s Protection Certificate #58 at Fall River, Massachusetts. This certificate gives his physical description as: Age 19, 5’ 2" tall, light complexion, light hair, and gray eyes. He made a total of seven whaling voyages, working his way up the chain of command, from greenhand to captain on his fifth and sixth voyages. His seventh and final voyage was on board the whaling ship Congress 2 as first mate, and evidently everything went smoothly until he decided to visit the natives on the island of Hiva-Oa. Having been warned by Captain Stranburg not to go ashore, he displayed a state of impetuousness, if not down right stupidity. Incidentally, on her final whaling cruise after leaving Hawaii early in June 1865, Congress 2 proceeded to the whaling grounds in the Bering Sea for one last hunt, before returning to New Bedford. There, on June 26, 1865, she was captured by the Confederate Cruiser Shenandoah and, along with fourteen other whaleships, destroyed. This was considered an act of piracy, because the Civil War had been over as of April 9, 1865, and the whalers should have been safe. The crews were not harmed, however, and were placed on board three bonded whaling ships that sailed for San Francisco and Honolulu. Oakdale, Connecticut, 2005 |