Pick from the Past

Natural History, September 1936

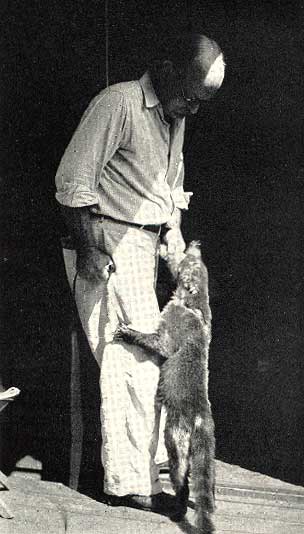

José—1936

|

FTER my

departure from Barro Colorado in April, 1935, José was adopted by the

laboratory family. Possibly, it would be more accurate to say that the

family was adopted by José. At any rate, seven months later I found

him occupying much the same position as a household cat, notoriously a spoiled

creature of independent ways.

FTER my

departure from Barro Colorado in April, 1935, José was adopted by the

laboratory family. Possibly, it would be more accurate to say that the

family was adopted by José. At any rate, seven months later I found

him occupying much the same position as a household cat, notoriously a spoiled

creature of independent ways.

Bananas, Please!

![]()

He had established his headquarters at the entrances to the laboratory and

kitchen, digging a slight hollow in the earth beneath the water tank in which

at times, he rested. From this retreat, when hunger prompted, he issued to

hold up whoever chanced to pass for food, meaning always bananas. His request

was wordless but made with unmistakable motions as, on his hind legs, he came

confidently forward. If no fruit was forthcoming he retired; if it was held

beyond his reach, he did not hesitate to climb for it and the marks of his

claws on one’s legs bore evidence to their sharpness and the strength of their

owner’s grip. This experiment was not repeated.

![]()

|

José had not been able to replace his injured eye, but his upper lip was in large measure restored, leaving a scar visible only to those who looked for it. Of his numerous bodily wounds there was no outward evidence while his general physical condition bespoke leisure, repose, and abundant food. José’s figure had indeed lost the slenderness of the wild individuals of his kind. He was, unquestionably fat and showed a marked disposition to sit or lie down when not in motion. I ended this degrading life of luxury by restoring the feeding-tray on the trolley from my balcony to the forest as José’s source of food. It was believed by those responsible for José’s increase in weight and apparent immobility that his avoirdupois would prevent him from performing the acrobatics which had so distinguished him the preceding spring. They were mistaken.

Finding that his demands for food were no longer honored José soon accepted my invitation to return to the scene of our first meeting. There he found no bananas offered him from indulgent hands but only the scent of bananas proceeding from places beyond his immediate reach. Seven months had passed since he had been confronted by this situation. Would memory assist him in meeting it or would he employ original initiative?

The odor of a peeled banana on my balcony rail evidently attracted his attention and, nose up, he “tried the air” in familiar fashion. At once he came to the balcony floor, leaving it and returning several times before he located the food on the rail. This was distinctly below his average performance of the preceding spring. And twice he visited the rail before he discovered a second banana on the crossbar of the three-foot upright to which the feeding-tray trolley wires are attached. This he climbed with some little effort, remaining on it to eat his reward.

He seemed to be aware of still further food in the feeding-tray about eighteen feet distant and started to walk the trolley wires toward it but after one step returned to the cross-piece and descended to the ground. Thirty minutes later he returned without hesitation for a fresh piece of banana on the crosspiece but made no attempt to go to the tray. In another half hour he again came to the cross-piece for the always acceptable banana. As before, he started on the wires for the tray but after a foot gave it up and retreated to the ground. But there was still banana in the air, and with characteristic coati persistence José soon returned to the cross-piece and finding no more banana there turned his whole attention toward the tray, where a lone banana remained. For the first time he now encountered the cord by which the tray was pulled to and fro. It was of the same kind as that used in various banana experiments with him the preceding spring and its touch seemed at once to arouse memories of bananas which had then always been attached to it. At once he pulled it vigorously and, when this brought no result, as before he bit it until I interfered.

This ended the tests for the day. They showed plainly that José was

far from losing either his mobility or initiative and that when the right cord

was touched his memory was responsive.

![]()

|

The following morning, November 30, at 10:50, José returned, climbed up the steps of the balcony where I was sitting, and came to me obviously for food. I referred him to the crossbar and tray where bananas awaited him. But for reasons, if any, known only to himself, he descended the two steps to the ground and went directly to the woods thirty feet away. Passing the tree to which the far end of the trolley wires are attached, and which was still encircled by the impassable zinc “rat-guard,” he started to climb the following tree but after ascending several feet slipped back to the ground. “Ha ha,” I said, “it’s too much for you,” but without pause he continued to the succeeding tree. Evidently it had required only two or three steps to show him that this second tree was not the right one. But on the third tree he obviously felt at home and confidently climbing to the point where it met the “trolley tree” he crossed over, descended that tree to the wire and without a moment’s pause walked out on one wire, resting his tail on the other, to the tray ten feet away. He acted as though wholly accustomed to the maneuver, ate his banana while resting easily on the tray, and then at once retraced his route to the ground. On this, his first trial, therefore, with only the slight, quickly corrected slip of starting up the wrong tree, he remembered his indirect route to the tray and followed it without difficulty. He did not, however, seem to climb as easily as in the preceding spring and, when ascending, stopped three times to rest a few seconds while panting rapidly. But within a few days he was an agile as ever. Why he should have balked at the wires the first day and treated them so familiarly the next I am unable to say. Possibly because at the forest end of the route to the tray they formed a regular part of an unbroken succession of events, while the balcony route was broken by various incidental experiences.

José’s Rivals

![]()

These two days served completely to restore the relations with José which

had been broken by my seven months’ absence. Meanwhile his existence had

become somewhat complicated by the appearance of several rivals for our favor.

These animals, known as Miguel, Julio, and Antonio, observing the ease with which

José supplemented the food supplied by the forest, had not hesitated

to advance their own claims for bananas and each found one or more patrons

among the workers on the island. But although these later comers were still

fed at the entrances to kitchen and laboratory they did not hesitate to poach

on José’s preserves at my balcony. When he was present they did not

venture to trespass, for they apparently recognized his seniority, and, in

a swinging gallop, always retreated before him. But José sometimes

had affairs of his own to attend to and when absent these trespassers soon

also learned to reach the various places in which I offered bananas to possible

bird visitors.

Within an hour after the feeding-tray had been cleared of the enveloping luxuriant vegetation of the wet season and supplied with a banana, it was visited by doubtless the same tanagers that had frequented it the preceding spring. They were soon joined by two blue tanagers and an adult female and young male of our summer tanager, wintering here. At times all three species were present together, an apparent recognition of family relationships or, at least, an exhibition of similar tastes, which resulted in a singularly beautiful picture. But if I expected to continue to receive these birds as guests I must find some way of protecting their dining-table from an intruder who would not hesitate to make them part of his meal. I therefore returned to the problem of making a coati-proof dining-table for birds. If a tray on two trolley wires could be reached so easily, possibly a tray on a single wire would be beyond a coati’s powers. Two wires supplied one for the feet and one for the tail, making a stable means of locomotion. But with the tail support removed, Mr. Coati would find himself strictly without visible means of balance. Moreover, recalling something about the super-skill required to walk a “slack rope,” I resolved that as a final deterrent my wire should be of the slackest. So I dropped it nearly four feet in sixteen, or to an angle of about twenty-three degrees, confident that the food-tray was now for flying creatures only, birds by day and bats by night.

With the Greatest of Ease

![]()

But José mastered the new contrivance at the first attempt. It is true

his little journey was ended so hastily that the tray turned over with him.

But he lost neither his head nor his footing while the banana was grabbed as

it swung above him and devoured before he resumed his journey upside down and

returned to the tree somewhat winded but experienced. After lunch the journey

was repeated with everything under control and it was evident that while I

had added to José’s skill I had in no way reduced his sources of food.

Thereafter, I tried to keep the tray so well supplied that there would be

enough bananas for both birds and coatis. But I did not confess myself defeated.

I still thought that there must be places open to winged creatures and closed

to quadrupeds and I looked to the trees.

| Two days served completely to restore the

relations with José which had been broken by my seven months’ absence.

Meanwhile his existence had become somewhat complicated by the appearance of

several rivals for our favor. |

Tying a banana at each end of a three or four foot string I tossed them to the outer branches of the trees over my balcony. Some barely caught and hung dripping from the terminal twigs as though they had grown there. Even the tanagers could reach them only while on the wing. And the coatis? I must confess that they made me feel as though I were lacking in both experience and imagination. For them I had merely substituted a banana for an almendro nut. They climbed down the branch as far as possible and if they could reach the string pulled it in with the banana at its end. Just, indeed, as they had pulled in the bananas attached by strings to the feeding-tray. If they could not reach the string they broke off the limb to which, directly or indirectly, it was tied and pulled that in. One pair of bananas landed at the extremity of a far-reaching balsa limb twenty feet above the ground and twice that distance from the trunk of the tree; but they were unerringly located and collected. Not one banana escaped.

Making It More Difficult

![]()

I deferred making the final experiment that occurred to me. Not because I believed

that it, too, would fail, but because of its general inappropriateness. Taking

a leaky zinc wash-tub I nailed it upside down on a stout pole about eight feet

long, of which two were firmly set in the ground. Bananas were placed on its

upturned bottom and there, at least, coatis tried in vain to get them. One

after another the younger animals climbed the pole to the heart of the tub

and dropped back to earth. But they were far from discouraged, and repeated

pawings at the rim of the tub finally so weakened its fastening to the pole

that it swung to and fro and a more than usually agile coati succeeded in getting

his claw over the rim and, in some inexplicable way, hoisted himself up on

to the bottom. In the end, therefore, not even the tub was immune and at this

point I abandoned further attempts. The coatis won. The birds must take their

chances. I would supply the bananas.

Meanwhile, I found that coatis were not restricted to a fare of bananas. With the ripening of the almendro nuts late in January they ascended the trees that bear them and no nut was too remote to escape picking. Only the thin rather acrid outer covering was eaten, then the nut was dropped for the peccaries, pacas, agoutis, and squirrels. This is a favorite food but even at the height of the almendro season coatis varied their fare. I was seated on my balcony one afternoon early in February when an unrecognized coati started sniffing about on the hillside near me. In a moment he was evidently assured that he had found what he wanted and began to dig. It was not a casual digging. It was a frenzy of digging. The earth, which had been in position only ten years, was comparatively loose and with stones nearly five inches in diameter it rose in a continuous eruptive shower that rumbled down the hill. Within five minutes the animal was lost to view in his own excavation. At the end of that time he withdrew his prize—a tarantula which, barring two claws, was devoured on the spot. The hole was thirty-two inches deep and fourteen inches wide at the entrance.

Fond of Eggs

![]()

There is a general, and I think, warranted belief that coatis are destructive

to birds, their nests and contents, but beyond their capture of a paroquet

at the laboratory I know of no instance of their bird-eating. As a means

of gaining more information we therefore placed two hens’ eggs where they

would be seen by wild coatis. Their action was prompt and definite. One egg was

soon carried unbroken to a distance of a hundred feet before eating, the

other was devoured on the spot. The top was neatly removed from each egg and the exposed

contents then lapped up as though from an egg cup. One could imagine that

such skill could be acquired only by experience, perhaps with tinamous’ eggs.

To vary this test I hid two eggs at different spots in the grass on the hillside near my balcony. One egg was not handled and was placed with the aid of a tablespoon attached to a long pole. It was never visited. The other was hidden by hand and visited frequently. Neither egg was taken and the experiment is mentioned only to suggest that it be repeated.

That an animal so fond of bananas should also have a pronounced if not indeed passionate liking for tarantulas helps prepare us for the statement that coatis are also fond of bats!

| A coati started sniffing about on the hillside near me.

In a moment he was evidently assured that he had found what he wanted and began a frenzy

of digging. Within five minutes he withdrew his prize—a tarantula which, barring two claws,

was devoured on the spot. |

When at night I explored the forest from my balcony with a powerful searchlight, its rays were often thronged by bats of several species. Some were fruit-eaters and in a steady line came for a bite of the banana in my food-tray. Others appeared to be insect-eaters, darting erratically here and there. To capture specimens for identification, like a great spider I spun my web, in the form of an Italian bird net, thirty feet long and six feet wide, between me and the forest. The bats caught were presumably fruit-eaters, which apparently lack the sensitiveness that aids insect-eating bats to avoid objects when in flight. But if they became entangled in a part of the net within reach of tree or hillside only the wings were left for me while a coati appropriated the still living body. I therefore abandoned this form of collecting and restricted further experiments on the food of coatis to cake and candy, both of which they refused. Of bananas, however, they never tired and even the ripest specimen was acceptable.

While José seemed in perfect physical condition it is clear that at the end of January, 1936, as the annual mating season approached, he was not as well prepared for its tests as he had been the year before. He was much overweight, a diet of bananas was doubtless not as strengthening as one more varied and more difficult of acquisition, and he was minus the eye lost in last year’s mating contests. Consequently, if there is any truth in the theory that an animal physically below par is seriously handicapped in the struggle for existence, José entered the lists of the 1936 mating season under a marked disadvantage.

José’s Marital Expedition

![]()

The result supported the theory. The date of his return from his marital

expedition demonstrated the regularity of his physiological cycle. It will

be recalled that in 1935, after an absence of two weeks, he returned to the laboratory

on February 11. In 1936, after a somewhat briefer absence, he returned on

February 10. In 1935 he was minus an eye and an upper lip and plus countless

body wounds, some of major importance. In 1936 he had lost the use of a foot, the remaining

eye was badly injured, a former shoulder wound was reopened to a length of

about four inches and width of over one, and there was literally not two

square inches of his body that did not show the mark of claw or tooth. José was,

indeed, such a pitiable looking object that the men urged me to end his suffering.

The injury to his foot was the most serious. It robbed him not only of an organ

of locomotion and means of securing food, but of a weapon. The foot was swollen,

its claws bent backward, and the care with which it was held from the ground

indicated that it was painful. Above all, José’s spirit seemed broken.

He had lost his distinguishing confident attitude toward life, and after eating

three bananas hobbled back to the woods, his lowered tail, like a flag at halfmast,

dragging behind him.

![]()

His Spirit Broken

The preceding year, after returning from his campaign of conquest, José had to contend only with his wounds. We supplied him with food and in the vicinity of the laboratory he found safety from his enemies. Meanwhile other coatis of his sex have made friends with us if they have not with him. If earlier in the year they interfered with what he evidently considered his prior rights, he exhibited his authority in a manner not designed to promote his popularity. Now it was their turn and they knew it; so did he. When in the morning he returned for his daily bananas he moved cautiously, advancing only after careful inspection of the surrounding territory. Even when eating he was constantly on the alert and would suddenly stiffen to attention if he fancied he detected the presence of an enemy. This act always impressed me as an exhibition of intelligent discrimination. Did he or did he not hear or smell one of his own kind?, it seemed to say. If he concluded that he did not, he resumed eating, but if he became convinced that an enemy was nearby, the half-eaten banana was dropped abruptly. There was no questioning growl, no “trying of the air” with that sinuous nose, no querulous twisting of the snake-like tail; without a word or a moment’s pause, tail dragging, he loped away in complete and shameless confession of his impotence.

But notwithstanding his evident desire to avoid further conflict, at least until he was better prepared to defend himself, it was apparent that he did not always escape. Often he showed new and more or less serious wounds and it was a question whether in spite of our care he would survive the attack of his foes. They showed him no mercy and about the laboratory, at least, appeared to be almost constantly on his heels. He could find no place where he was secure. March 3, for example, after eating four bananas on my doorstep he entered and crossed my room as though he were considering it for a retreat. But something, perhaps the confinement of four walls, evidently worried him. I stood one side to let him choose his own resting-place but he seemed in constant fear of an assault from the rear and returned to the door. Crossing the balcony to descend the steps he stopped suddenly head down, body trembling, as though about to collapse. Twenty feet away a coati was coming slowly toward him. José made no attempt to escape. He seemed to be ready to surrender. The approaching animal was one of the younger ones that he had dominated earlier in the season. José, I felt, would be helpless in his claws, so I drove him back to the forest and tried to induce José to return to my room. But this was a form of retreat he did not understand. So he pulled himself together, went down the steps and slowly climbed the hill away from his enemy.

A Fierce Encounter

![]()

Three days later an animal that I recognized as Miguel, after I had driven

him off several times, charged José while I was feeding him at the laboratory

door. The attack was made from the rear with a sudden, deadly ferocity and

José responded with a power and drive that we had not supposed remained

in his torn body. Miguel, evidently as much surprised as we were, quickly gave

way and we completed his rout. Then to illustrate that such little incidents

are all part of a coati’s daily life, José, with complete composure,

returned to the banana he was eating from my hand. I showed far more excitement

than he did.

| But notwithstanding his evident desire to

avoid further conflict, at least until he was better prepared to defend himself, it was

apparent that he did not always escape. Often he showed new and more or less

serious wounds and it was a question whether in spite of our care he would survive

the attack of his foes. |

Meanwhile José was making a marvelous recovery from his countless wounds. What is it, one asks, that keeps his scratches, cuts and gashes free from infection? Certainly the tongue, with which alone they are washed, bears no visible healing ointment but carries the essence of one wound to another, and all alike are without traces of pus or inflammation. How places beyond the reach of his tongue were treated I do not know. [Since the above was written I have discovered the following in Science for June 26, 1936: “Licking their wounds, a practice universal among animals, has good bacteriological justification, is reported by Dr. Herman Dold, professor of hygiene at the University of Tübingen. Cultures of bacteria to which saliva was added failed to thrive, while untreated ‘control’ cultures grew flourishing colonies of the germs. It therefore appears likely that in addition to keeping dirt and hair out of their wounds by the constant licking, the afflicted animals are so applying an effective antiseptic.”] His foot alone seemed inflamed and sore but here there had been an apparent tearing of ligaments which called for replacement of claws, and possibly bones, before healing, and while progress was made it was slow. It was not until March 11 that I saw him attempt to use his injured foot, other than to walk on it. Then he dropped a banana half-eaten and sniffing along the hillside made a half-hearted attempt to unearth a tarantula. The act seemed to say “I’m tired of bananas; give me some real coati food.”

During this period of daily visits José and I established closer relations than had previously existed between us. Hitherto I had been merely a source of bananas of which my hand was the container. Now he acted as though there was something in our relations besides bananas. He recognized my voice and responded to his name, coming to me, when hungry, from distances up to a hundred feet. He acted as though at home in my study where, his hunger appeased, he spent hours, chin on paws, comfortably sleeping in evident belief that he was safe there. Thus he clearly looked to me for protection as well as for food.

José’s Trust

![]()

When feeding he no longer grabbed the banana from my hand and made off

with it but gently put his paws on mine and with apparent care to avoid

injuring me with either claws or teeth, ate slowly. In short, within limitations,

José and I had acquired confidence in one another. Knowing that since

he had left his mother’s side he had never been touched except with intent

to kill, I made no attempt to caress José, nor did I expect anything like a purr

or friendly tail-wag from him. To be known when we met away from the

laboratory was the extreme form of recognition I expected.

On the morning of March 29 I met him near the lake digging with one foot for tarantulas. He stopped work as I approached and came toward me with an expression which I interpreted as saying: “You haven’t a banana about you, have you?” But before I could explain that I had not expected to meet him, etc., he smelled his own reply and returned to his digging.

Two days later, knowing I would pass this way, I placed a small banana in my sack on the chance of meeting José again. Sure enough, there he was hopping down the hill toward me, the injured foot held high. This time his expression read “What about that banana?” and I replied “Well, what about it, José?” He sat there on his haunches waiting for me to make the next move, but as I remained motionless, he came forward, went direct to the bag at my side, extracted the banana and ate it at my feet. He did not ask for another, for he knew as well as I that there were no more. Then he went into the forest but soon returned to hunt grasshoppers about me as though he sensed a safety zone in my vicinity.

His Only Friend—Man

![]()

As the time for my departure at the end of April approached, José was

returned to his friends at the kitchen door. New fur was sprouting from the

bare patches on his body, but he could not hope for a new eye, and I doubt

if ever again his foot will serve him as an effective weapon. With our bananas

and his discretion he may survive until another mating season brings with it

the desire for a mate and forces him to re-enter the lists. Then the loss of

a foot, as well as an eye, will prove too great a handicap and José will

meet the end of the male of his species. But he will have added to our knowledge

of a coati’s life. His sisters, in due time, doubtless had families of their

own, but since reaching maturity José’s only contacts with his

kind have been to fight and to mate. Aside from these brief periodic

exhibitions of animalism he is alone in his world. In sickness and in hunger he is

dependent solely on himself. Other forms of life may serve him as food;

with man alone can he hope to make friends.