Natural History, November-December 1929

A Collector in the Land

of the Birds of Paradise

Collecting Brilliantly Colored Birds Among the Mountains of

New Guinea—The Problems and Difficulties of an Ornithologist

in the Savage Interior of One of the Greatest of Islands

By Rollo H. Beck

Leader of the Whitney South Sea Expedition

![]()

With Illustrations by Francis L. Jaques

![]()

[See slide show photo gallery.]

After sixteen years of arduous adventure in the service of the American Museum of Natural History, Mr. Rollo H. Beck and Mrs. Beck had started homeward from the Solomon Islands in June, 1928. They looked forward to retirement and a well-earned rest in their California home. The heat, and danger, and swelter of nearly a decade among the far-flung islands of the South Seas, during the period of Mr. Beck’s leadership of the Whitney South Sea Expedition, was soon to become only a memory in which happy episodes would crowd out any less pleasant to remember.

Mr. and Mrs. Beck had not even reached Sydney, Australia, on their homeward way, however, before a wireless message overtook them, proposing an additional year’s work on the mainland of New Guinea. A study of the birds of paradise was among the naturalist’s temptations mentioned in the message and, despite their homesickness, Mr. and Mrs. Beck turned northward again as soon as they had outfitted in Australia. Some of their experiences during the subsequent year are related in the following account, in which Mr. Beck tells of the discovery of a bird of paradise new to science, all the more remarkable because it was obtained in territory supposedly exhausted of such ornithological surprises.—Robert Cushman Murphy

bird of paradise called far across the cañon from our hut in Meganum, a little native village, twenty miles inland from Madang, the principal mainland port of New Guinea Territory. From far up the cañon another answered, and many times a day during the next six weeks we heard the strident calls of the yellow-plumed bird of paradise (Paradisaea minor finschi). Shortly after our arrival, Manube, our first shootboy, strolled out for a couple of hours, and brought in the first three specimens of this species, all of them fine males, with the flowing plumes so beloved by the milliners of twenty years ago.

The absence of these three individuals from the vicinity of our camp could not be detected by any decrease in the volume of paradisian sound that was audible daily, so we classed the species as common.

Baker’s Bower Bird (Xanthomelus bakeri)—Adult male and young male of one of the new species discovered by Mr. Rollo H. Beck near Madang on the northern coast of New Guinea. The female is still unknown.From several sources in the Territory I was told that most of the former German owners of plantations along the coast had paid for the clearing and planting of their properties by selling bird of paradise skins. At one port in the Territory several dozen old commercial skins were offered to me, but the law against killing and exporting this family of birds appears to be well obeyed at present, for within five miles from where these skins were offered I saw several and heard many of the same species.

That at least one New Guinea resident hopes for a repeal of the present drastic prohibitory law was evidenced by a communication sent recently to a Sydney (Australia) paper, wherein damage to cultivated crops in one section of the Territory was laid at the door of marauding birds of paradise. During my stay in the Territory I heard literally hundreds, dozens of these close to native gardens, but not one did I see feeding on cultivated plants.

The usual food of several species, determined by stomach examinations, was apparently wild berries of various kinds.

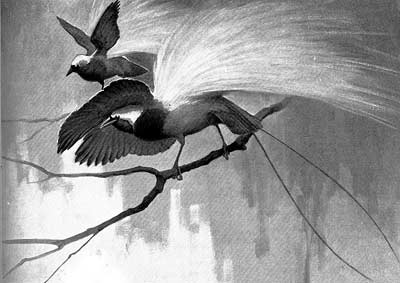

A Six-Plumed Bird of Paradise (Parotia wahnesi)—The beautiful jet-black body-feathers of this bird are topped by six plumes, also jet black. A tuft of bronze feathers grows directly over the bill, and the throat has an iridescent sheen of green and purple. One of these birds is here pictured in partial display.From the point of view of an experienced bird collector, Meganum is not an ideal collecting point. Nowhere on the various trails round about can one find a level stretch of ground fifty yards long. It is either steeply up or down, and birds of paradise as well as other species prefer the larger and highest tree tops to those within reasonable shooting distance. My first bird of paradise was a lucky fluke. While I was walking along a trail through high forest trees, a bird called ahead of me and I answered with a crude imitation. A small brown appearing bird lit over my head and a moment later dropped at my feet. Not till I stooped to pick it up did I see the long, gray, curled tail feathers, and it was much more surprising to see the same curling feathers change to dark metallic blue when their upper surface was viewed. But the multitudinous colors of the bird when held in hand made one wonder where one’s eyesight could have been when only a dull brownish bird had been the apparent target. Rich green were the underparts, while brown, yellows, and grays in various shades and patches marked the upper parts. A page would be needed to describe the color combinations of the back alone. This beautiful creature has been burdened with a name which is spelled Cicinnurus regius similis.

Later in the day a loud call and swishing wings drew my attention to a dark-colored bird that lit close to me. This proved to be another species of paradise bird, the rifle bird. Its shiny blue throat color changed to purplish green on the breast, while the velvet black back merged into a metallic blue crown on the head. When feeding, this species often works down to the smaller trees of the heavy forest, but ordinarily it keeps to the higher parts of the largest trees. One bird that I kept hearing every half hour or so for several hours, changed his perch a dozen times during that period, but did not fly out of a half-mile radius from the original perch.

Each male of this species seemed to me to have a definite area in which he moved, for, on several of my visits to a given locality, I would hear the same bird calling. Although I frequently tried to see certain individuals that I could hear calling in trees near by or mayhap directly overhead, only on rare occasions could the bird be observed. Sometimes the loud swish of the wings would give me notice of their passing in the forest, and on those sounds I based most of my attempts to get within reach of the elusive quarry. An interesting point, to me, about this species was the altitude at which it ranged at different stations. At Meganuin, and at Keku, a station forty miles south of Meganum, not one of these birds was heard, until a height of more than two thousand feet was attained. Behind Finschhafen, one hundred and fifty miles or so south of Keku, I was surprised to hear one at five hundred feet, and others frequently below two thousand.

Prince Rudolf’s Blue Bird of Paradise (Paradisornis rudolphi)—Wholly unlike the usual attitude of display is the performance of the blue paradise bird. He hangs from the perch by his feet, spreading the feathers of breast and flanks into a living fan. Across this blue fan run bands of black and rufous.Only at Finschhafen did I have an opportunity to pass above the range of this species, the mountains about the first two camps exceeding little more than three thousand feet. This height was the extreme limit beyond which no birds were heard when I worked inland from the port of Finschhafen. How closely birds keep to certain bounds was illustrated by the vociferous calls of another bird of paradise (Paradisaea guilielmi). This species begins to make itself heard plentifully at about twenty-two hundred feet, where it replaces a related species that inhabits the forest in the lower zone. From twenty-two it is heard regularly up to four thousand, where it abruptly stops. We spent some time at Zagaheme, which is four thousand feet and, though we heard and saw the birds often about the village and below it, when I climbed up a few hundred feet on the ridge behind the settlement, the bird was missing, even though I could hear it calling a thousand feet below my trail.

At Zagaheme three birds of paradise new to me appeared. My acquaintance with one of them began when I crossed trails with my shootboy about noon the first day. He was accompanied by a small boy carefully carrying (by a thread run through the nostrils) a long-tailed black bird which had a collar of burnished gold, separating the black of the throat from the bright green of the breast.

Another blackbodied bird had three long feather vanes tipped with tiny black feathers extending to the base of the tail, the vanes coming from just back of the eyes. A metallic patch of light green or dark blue feathers (depending on the angle at which the light struck them) covered the lower throat.

Augusta Victoria’s Bird of Paradise (Paradisaea apoda augustae-victoriae)—This bird, shown also on the cover of Natural History in full color, is among the most gorgeous of all the birds of paradise. In display the male stands on the perch with wings raised and long flank-feathers greatly expanded.The third bird of the list was also blackish. Its throat was blue and had long points sticking out somewhat after the fashion of the present-day collars that I find New Yorkers wearing. In addition to the pointed collar, this bird sports a beautiful ruff of soft, velvety feathers, which it raises or lowers as occasion demands. Whether these three species live much above six thousand feet I did not determine, my trips to seven thousand and above being too few to form an opinion. It was disappointing to me to find no specimens of the blue bird of paradise, its range beginning about five thousand above sea level. Apparently it does not range so far to the north, as none of the natives seemed to be acquainted with it.

Contrary to the habits of most species of birds, the females were the more curious when investigations were to be made. Often a female would drop down quite close to me to have a good look, while the brightly colored male, if seen at all, would he flitting about high above. In addition to the birds of paradise, pittas, smallsized ground birds, were on my list of extra desirable specimens. Although they were not rare, they proved to be very adroit in their movements.

Had it not been for some small boys at Keku whom I interested in trapping for me, the series would have been very meager. These youngsters built miniature duplicates of their fathers’ pig traps in the forest, and by baiting with big grasshoppers or ether convenient bird food, succeeded in capturing several of two species of pittas. They surprised me by bringing in also a number of kingfishers, caught in the same manner. In fact they brought me more longtailed kingfishers (Tanysiptera hydrocharis meyeri) than I captured with the shotgun, although later I found it much easier to locate the kingfishers sitting in the forest. Often the slowly waving tail would be my first intimation that one of these beautiful birds was right in front of me. One evening after dark one of the boys working at a mission station brought in to me a freshly killed specimen of the blue-bibbed pitta. I asked him where he got it and how. He explained as follows:

Twelve-Wired Bird of Paradise—The twelve wires of the male, Seleucides ignotas, are recurved feathers with stiff, bare shafts, growing among the lengthened flank-feathers. The black portions of the plumage are glossed with green on the back, purple on the crown, wings, and tail, while the breast has scaly feathers with metallic green tips. The lower parts are yellow. The female is more soberly colored.“Bello, now me go drink water. Mama belong keow runaway. Me lookim, now me come back. Long night time me go ketch im. Me come me giv im you.”

Translated to plain English all this means:

“When the noon horn sounded I went down to the brook for a cool drink and saw a bird run away from its nest. I saw eggs in the nest, so at night time I went to it and caught the parent, bringing it to you.”

This meritorious act earned for the boy a stick of tobacco and enabled me to get a photograph of the nest and an egg of the bird, one of the two the nest contained being broken when the bird was caught.

Glancing casually at the nest in situ, nine out of ten persons would see merely a jumble of dead leaves and the usual litter which had fallen about the rotting log, while an öologist looking for nests would likely note the structure and give it the second confirmatory glance. It was tucked away under a large decaying branch, in a shallow hole in the bank,

and had at the sides and bottom long dead leaf stems as if they had fallen naturally. The roofing was cunningly composed of fresh green fern leaves and intermingling dry leaves in the usual forest proportions. Inside there was a thick lining of fine black rootlets on which the creamy spotted eggs showed plainly.

A Superb Bird of Paradise (Lophorina superba Iatipennis) is here beginning to display his iridescent shield. His plumage is jet black with a bronze luster on the cape, and crown and breast-shield metallic green.While sitting before the nest writing this description in my notebook, a tiny kingfisher cheeing through the forest lit over my head for the time it took to turn my eyes toward it, and then darted on its invisible flight to another perch. A larger kingfisher (Alcyone azurea lessonii) similarly colored, which flies up and down the mountain streams, reminded me often of the flight of dippers in California mountains, but the tiny one has its counterpart only in straight-flying humming birds, for by the time its call reaches the ear, the bird itself is yards away, chee cheeinq as it goes.

One of the little birds that I always listened for was the pygmy parrot, two species of which I took in New Guinea. Its note is a most elusive scree scree, and frequently, although hearing the note regularly, I could not focus my eyes on the spot on the near-by tree trunk where the bird was. From the hotel porch in Rabaul the capital of the Mandated Territory, I watched several times the feeding actions of the green species, while they worked up and down and under the limbs of the trees within twenty feet of me.

They repeatedly pulled off small bits of the dry bark, but just what they found underneath I could not determine. Like some species of kingfishers these little parrots use an occupied termite nest for their home. A cavity in one side of the nest appears to keep dry, even in heavy rain squalls. Just how they keep clear of the thousands of termites has never been explained to me satisfactorily.

This was just one of the many interesting, incidental questions that puzzled me on the New Guinea trip. There were many others, and still more await future collectors to the unknown mountains in the interior of that great island.