Natural History, May-June 1928

“Robinson Crusoe’s Children”

The Strange Story of Nine English Mutineers Who, More Than a Hundred Years Ago, Took

Up Their Abode With Their Native Tahitian Wives, on a Desert Island in the South Seas—The

Life and Heredity of the Descendants of These First Settlers on Pitcairn and Norfolk Islands

By H. L. Shapiro

Assistant Curator of Physical Anthropology,

American Museum

N two remote South Sea Islands, Pitcairn and Norfolk, dwell the descendants of the notorious mutineers of the “Bounty.” With only intermittent contact with the outside world, this two-fold colony has maintained its integrity for almost 140 years. The physical anthropologist could not ask for a more interesting group with which to work.

N two remote South Sea Islands, Pitcairn and Norfolk, dwell the descendants of the notorious mutineers of the “Bounty.” With only intermittent contact with the outside world, this two-fold colony has maintained its integrity for almost 140 years. The physical anthropologist could not ask for a more interesting group with which to work.

|

Even in these days of short and comparatively luxurious voyages, it is easy to imagine the great delight of the sailors on landing at one of the pleasantest of the South Sea Islands, where both Nature an the natives were kind. Bligh, in his journal published some years later, speaks of the rapidity with which each sailor soon had his particular “tyo” or friend, who acted as host during their stay at Tahiti.

After six months spent in collecting breadfruit and other indigenous plants, Bligh set sail from Tahiti in April, 1789. The partings were long and melancholy, and it was with evident reluctance that the crew set their sails to the breeze which was to carry them away from the scene of six happy months. Added to the discontent engendered by these farewells, was the familiar harshness of Bligh. One of the sufferers from Bligh’s behavior was Fletcher Christian, the mate, who on several occasions had felt the lash of his captain’s tongue. We can never know the true cause of the mutiny, but we may guess that the resentment of Christian found a ready response in the crew, discontented with their master and at leaving Tahiti.

Early on the morning of the 28th of April, the “Bounty” was in the neighborhood of the Tongan or Friendly Islands, when Captain Bligh was forcibly awakened by several armed men and discovered that he was a prisoner on his own ship. In his journal he recorded that he was entirely unaware of any mutinous feelings among the sailors, and from other evidence it seems that the mutiny was spontaneous. All Bligh’s efforts at persuading the men to give up their design were unavailing. At each attempt he was ordered to hold his tongue or he would be a dead man. Eighteen of the crew who were not in the plot were also taken prisoners, and the Captain and his faithful men were put adrift in a small boat weighted down almost to the gunwales. Only scanty provisions, consisting of 150 pounds of bread, 32 pounds of pork, 6 quarts of rum, 6 bottles of wine, and 28 gallons of water, were furnished.

|

Christian, at the head of the twenty-five mutineers, now returned to Tahiti, where they accounted for Bligh’s absence with the story that he had met with Captain Cook, and that the “Bounty” had been sent back for more supplies. After several unsuccessful attempts at establishing a colony on a near-by island, Christian and the mutineers returned to Tahiti, where they separated into two parties. Sixteen of the men preferred to remain at Tahiti where they very soon set up menages. The other nine, anxious to find an inaccessible island where they might be safe from a punitive expedition from England, left Tahiti, taking with them about twelve native women and six native men.

When Captain Edwards of the “Pandora,” sent to capture the mutineers, reached Tahiti a couple of years later, nothing was known of the fate of Christian and his men.

Not until 1808 was a trace of the missing men discovered. In that year Captain Mayhew Folger of Boston was very much surprised to find himself hailed in English by the children of the mutineers when he touched at Pitcairn, which he believed to be uninhabited. He learned from the sole surviving male, John Adams (formerly Alexander Smith), that on reaching Pitcairn in 1790 the “Bounty” was destroyed so that there might be no defection. Each of the nine sailors received an equal allotment of land.

Owing to the treatment which the native men received at the hands of their white companions, they soon rebelled. Dissension among the sailors on account of the women and fighting with the native men led to a series of horrible and brutal crimes, which ended in the murder of all the native men and all but four of the sailors. Of these, M’Coy, who in his youth had worked in a Scotch distillery, discovered the intoxicating qualities of a distillation of the ti plant. It was reported that he jumped over a cliff in a drunken frenzy.

|

So unexpected and dramatic was the idyllic life of the Pitcairn Islanders after the violence which attended its establishment, that this remote island and its inhabitants served many a preacher for a text on the beauties of a Christian life. Rare copies still exist of a small pamphlet distributed among American Sunday Schools early in the Nineteenth Century which related the story of the Pitcairn Islanders for the edification of young readers.

Except for the rare arrival of a ship, the calm of Pitcairn was unbroken. In 1831 the islanders made an attempt to establish themselves on Tahiti, where they might have more room for expansion. This ended in disillusionment and a return to Pitcairn. Nothing more was done about the dread of overpopulation, which motivated the move to Tahiti, until 1855, when they petitioned the British Government to remove them to Norfolk, which was being abandoned as a penal island. Consequently in 1856 the whole community was transferred to its new home on Norfolk, where for the first time they saw stone buildings. Although Norfolk is considerably larger than Pitcairn, and its beauty attracted many of the islanders, some of the colony were homesick for Pitcairn. After a few years several families returned to Pitcairn, where their descendants still live. But the principal group still dwells contentedly on Norfolk. Some years afterward, against the wishes of the islanders, the Melanesian Mission established a station on Norfolk, but recently it was abandoned.

|

The only men of education and learning died or were soon murdered. John Adams was almost illiterate, tracing the meanings of words with great difficulty, and he had no knowledge of government or law. Consequently it is remarkable to trace the development of a workable code of self-government and conventions. Almost from the beginning the women had an equal share with the men in the election of the officials who took over the guidance of the colony after Adams’ death in 1829. Property was inherited alike by all the children regardless of sex. Education was compulsory up to the age of sixteen. This consisted in learning to read, write, and cipher, with a great deal of Biblical history. For a time there was a communal fund of food to which all contributed. Later, when trading assumed greater proportions, definite regulations were adopted to govern the methods and standards of exchange.

The houses were built in an original fashion. The planks were placed vertically in grooves cut into large timbers which made the frame of the house. Some were two stories in height and were grouped about a central commons. The clothing was made by the women from tapa manufactured according to Tahitian methods, although later they were able to secure clothes from whalers and others who visited them. The manner of cooking was very reminiscent of Tahitian cooking. A whole pig would be baked in a pit dug in the ground and covered over with a mat of leaves.

One of their most interesting contacts was with the New England whalers who swarmed in the Pacific in the middle of the last century. Many of the young men shipped on long cruises, returning with Yankee tricks of speech and customs. Frequently the captain would leave his wife at Pitcairn to be picked up on the return voyage. During such visits these efficient New England housewives introduced many innovations, so that even at the present time pie is a favorite dish. During my stay at Norfolk I was the guest at a Thanksgiving dinner at which all the traditional dishes were served.

One of the most valuable things inherited from the whalers is the technique of whaling. On Norfolk, whaling is still practiced and is a lucrative source of income.

Since the necessities of life on Norfolk and Pitcairn are few, the principal occupation is raising sufficient food to supplement the wild fruits that grow abundantly. An additional source of income on Norfolk is the preparation of lemon juice, which is shipped to Sydney, Australia.

For entertainment the Norfolk Islanders are dependent on European games and amusements. Tennis is a favorite form of sport, and a tournament is held annually for a shield. Cricket, football, and horse racing are also popular. More sedentary games such as checkers, cards, and chess, find enthusiastic devotees. During my visit a weekly dance was held, which attracted all the younger people. Also once a week a moving picture show was given. The social life of the islanders is very hearty and informal. Moonlight picnics, garden parties, and other gatherings of a social nature are always hilarious. A strong love of music is common, and one of the most generally attended organizations is the choral society.

|

Most of the islanders are affiliated with the Church of England, but other denominations such as Methodist, Seventh Day Adventist and Baptist have adherents. Pitcairn, however, is now almost entirely Seventh Day Adventist. The principal church on Norfolk is a large Georgian building of gray stone which is a relic of the penal colony. On alternate Sundays the congregation meets at the former chapel of the Melanesian Mission station, which is beautifully decorated with mother-of-pearl, inlaid in Melanesian designs, and has a number of beautiful stained glass windows designed by Burne-Jones.

The present population is approximately 600 on Norfolk and more than 175 on Pitcairn. Many of the younger members of the community have in recent years sought wider opportunities on the mainland, where they have married and settled, so that the total number of living descendants of the mutineers is probably more than a thousand.

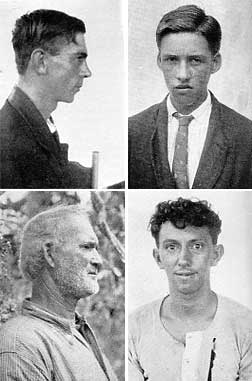

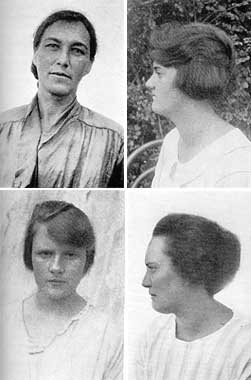

To the anthropologist, the chief interest of the descendants of the mutineers of the “Bounty” lies in the fact that here is an example of race mixture between two contrasted races. In studying race mixture it is always discouraging when one attempts to define the ancestry precisely. Where the mixture has been long continued, it is frequently hopeless to obtain satisfactory genealogies. The Norfolk Islanders, however, have kept records of marriages and births, so that I have been able to make for all the islanders genealogical tables which go back to the original cross, and in that way determine the proportions of Tahitian and English in the population. There is somewhat more English “blood” in the present generation. In studying the qualitative characters such as eye color, skin color, and hair form and color, one finds among these hybrids evidence of genetic behavior along Mendelian lines. The typical phenomena of dominance and segregation have taken place. In a small proportion the recessive traits such as blue eyes, blond hair, and fair complexion, are combined in one individual. On the other hand, one finds, according to expectation, a number of individuals who are strikingly Tahitian in appearance. On the whole, Tahitian and English characters form a mosaic, the totality of which in some tends toward the English and, in others toward the Tahitian.

|

|

|||||||

From necessity the islanders have inbred from the beginning, so that now after five or six generations, everyone is related to the rest of the community. In some cases the degree of blood relationship between husband and wife is extremely close. Yet there are no evidences of deterioration. On the contrary, the Norfolk Islanders are tall, muscular, and healthy. That inbreeding mysteriously produces degeneracy is now disproven by animal experimentation. Among the Norfolk Islanders we have another example that inbreeding in a sound stock is not attended by the traditional stigmata of degeneration.

Vital statistics reveal some interesting physiological facts in the hybrids. In the second generation the average number of children per family was 9.1. This average is greater than in any other generation. In the same generation the average age at marriage was 16.8 years for the women and 20.9 for the men. In later generations these ages increased. This high point in fertility exceeds the fecundity even of the Rehobother Bastards studied by Fischer.

Although there have been several additions of Europeans to the Norfolk community, their influence has been relatively slight. One can only hope that this fascinating group may be allowed to maintain its identity and continuity.