Natural History, May-June 1927

The Antiquity of Man in America

By J. D. Figgins

![]()

Director, Colorado Museum of Natural History

HEN we analyze the technical opposition to the belief that man has inhabited America over an enormous period of time, we find it is not only restricted to an individual minority, but it also appears to be traceable to the results of a too circumscribed viewpoint, a failure to appreciate properly all the evidence, and a seeming unwillingness to accept the conclusions of authorities engaged in related branches of investigation. It is a fact, of course, that the nature of the material evidence upon which opinions are based is an important factor, and when such evidence is not abundant, it is obvious that students cannot successfully restrict their studies if they would avoid the dangers that arise through a lack of continuity in one or more threads of evidence.

HEN we analyze the technical opposition to the belief that man has inhabited America over an enormous period of time, we find it is not only restricted to an individual minority, but it also appears to be traceable to the results of a too circumscribed viewpoint, a failure to appreciate properly all the evidence, and a seeming unwillingness to accept the conclusions of authorities engaged in related branches of investigation. It is a fact, of course, that the nature of the material evidence upon which opinions are based is an important factor, and when such evidence is not abundant, it is obvious that students cannot successfully restrict their studies if they would avoid the dangers that arise through a lack of continuity in one or more threads of evidence.

This appears to be very well illustrated by individuals learned in physical anthropology, comparative craniology and racial relationships. The chief denials of man’s antiquity in America appear to have their origin in those sources of investigation. Such criticism would doubtless have weight and value were skeletal evidence abundant. But such evidence, representative of the periods antedating that which is regarded as “modern,” or since Pleistocene times, is exceedingly meager. Indeed, it is far too scant to make possible intelligent comparisons and safely arrive at definite conclusions. Therefore, to be of value, it is essential that it be supplemented by those branches of the sciences that are capable of fixing geologic time periods—the sole means of bridging the weaknesses that occur in the thread of evidence represented by skeletal remains. Without this aid, opinions are not only venturesome, but distinctly misleading, if given publicity.

Readers of the discussions relative to the antiquity of man in America must frequently wonder because of the antipathy for the acceptance of evidence of that character, and often they may have inquired “Why should we not expect to find such evidence, since there are neither conditions nor facts that interfere in the slightest with such an expectation?” Obviously then, denials of the antiquity of man in America, without convincing proof that we could not expect to find such evidence, are purely supposititious.

However, the purpose of the present paper is not a discussion of the relative merits of arguments previously advanced, but a presentation of new evidence of man’s antiquity in America. As the writer has not made a special study of this subject, his opinions regarding the importance of the evidence would be valueless, and for that reason he expresses none. He merely views it in the light of substantiating earlier finds of a like and similar nature, and as pointing the way to other and more important discoveries. His task is the recording of the facts as he knows them.

In 1923 Mr. Nelson J.Vaughan, a resident of Colorado, Mitchell County, Texas, in a letter to the writer, described a deposit of bones in the bank of Lone Wolf Creek, near his home. Upon request, Mr. Vaughan forwarded examples to the Colorado Museum of Natural History for determination. These proved to be fossilized parts of an extinct bison, and the following season, 1924, Mr. H. D. Boyes was sent to the locality for the purpose of making excavations.

After the removal of the overlying formation (studied and elsewhere described by Mr. Harold J. Cook, honorary curator of palæontology, Colorado Museum of Natural History) and the finding of portions of the skeletal remains associated, it was deemed most expedient to remove them in sections. This was accomplished by working down until the fossils were exposed, cutting channels through the deposit at intervals, thus forming “blocks” of considerable size, these, in turn, being encased in burlap and plaster of Paris. A heavy crate was then introduced, and when a block was firmly fixed in the latter, undercutting took place. Then, with the use of tackle, the blocks were released from their bed and turned on edge for the purpose of removing the excess matrix, and planking over the bottoms of the crates. During these operations, the nearly complete skeleton of an adult bison was uncovered, quite articulated and lying on its left side. This was divided into sections and taken up as described above.

|

Independent of the lost arrowhead, which is described as very similar to the first, two artifacts were taken from beneath an articulated and fossilized skeleton of an extinct bison. That Mr. Boyes seems not to have recognized the full importance and significance of these finds is suggested in his permitting the loss of the second example—whether through theft or otherwise—and the fact that he did not make an immediate report of them. The first intimation the writer had of their discovery came through a visitor to the Museum, who had been present when the first arrowhead was uncovered. Replies to inquiries and later verbal details by Mr. Boyes verified and enlarged upon this account in all particulars.

|

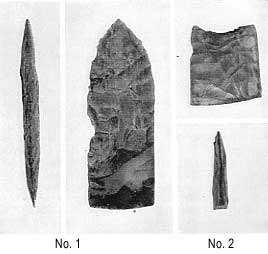

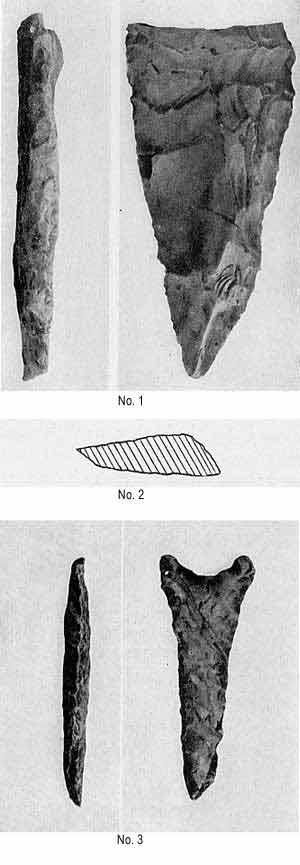

As critical studies of the artifacts found associated with the bison remains near Colorado, Texas, must be left to the archaeologist, but brief detailed mention of them will be made here. There are two or three private collections of arrowheads that were picked up on the surface in the vicinity of Lone Wolf Creek, all of which have been examined by Mr. Cook and Mr. Boyes. None contained examples approaching in similarity, either in form or workmanship, those found with the bison skeleton. The latter are of grayish flint, quite thin, as shown in Fig. 1, and are devoid of evidence of notching, which is distinctly opposed to the forms found on the surface in that locality. Equally distinctive is their superiority of workmanship which, I am told, also applied to the example that was lost. While there seems to be no doubt that these artifacts represent a cultural stage quite distinct as compared with that revealed in the arrowheads found on the surface, it is not the writer’s intention to discuss such questions, and he will refer to the similarity of this find to that made by Mr. H. T. Martin at Russell Springs, Logan County, Kansas.

Readers who have been interested in the subject of man’s antiquity in America, are, no doubt, familiar with this discovery, which was made by Mr. Martin in 1895, and while the writer has not examined this artifact, Mr. Martin kindly sent a photograph for reproduction here; this for comparative purposes. (Fig. 2.) Dr. F. A. Lucas applied the specific name occidentalis to the race of bison with which this artifact was associated.

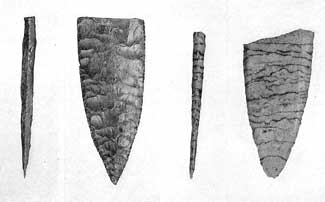

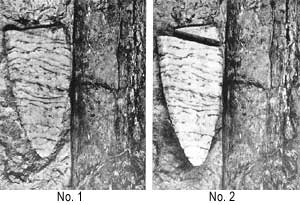

During the summer of 1925, Messrs. Fred J. Howarth and Carl Schwachheim of Raton, New Mexico, informed the writer of a quantity of bones exposed in the bank of the Cimarron River, near the town of Folsom, Union County, New Mexico, Later, those gentlemen forwarded examples for examination, which proved them to be parts of an extinct bison and a large deerlike member of the Cervidæ. Accompanied by Messrs. Howarth and Schwachheim, Mr. Cook and the writer visited the locality in April, 1926, and after a study of the deposit, made arrangements with Mr. Schwachheim for the removal of the overlying formation, consisting of some six to eight feet of very tough, hard clays. In June the writer sent Mr. Frank M. Figgins to supervise the removal of the bones, in which work he was aided by Mr. Schwachheim.

|

|

Until the studies now in progress are completed, the geological age of the Folsom bison will not be known. That it is of an extinct race there is no question. (Dr. O. P. Hay has kindly consented to study all of the bison material that was obtained in Texas and New Mexico, and expresses the belief that it contains three undescribed races.)

We have, then, in the Folsom arrowheads, the third instance of a very similar type of artifact being found immediately associated with extinct bison, in circumstances which lead geologists and palaeontologists to conclude that they belong to the Pleistocene age.

Having read an article dealing with the question of man’s antiquity in America by Mr. Harold J. Cook, which appeared in the November, 1926, number of the Scientific American, Dr. F. G. Priestly of Frederick, Tillman County, Oklahoma, wrote Mr. A. G. Ingalls, editor of that publication, briefly describing the finding of artifacts associated with fossil mammal remains in that vicinity. After some correspondence, and with Doctor Priestly’s consent, Mr. Ingalls forwarded this letter to Mr. Cook. Doctor Priestly’s account of these discoveries was of such a convincing nature that it could not be doubted that the Oklahoma material was of great importance. With the view of making studies of both the material and physical character of the deposits from which it was taken, Mr. Cook and the present writer joined Doctor Priestly at Frederick in January.

It was at once apparent that while Doctor Priestly recognized and understood the importance of the finds he described in his letter to Mr. Ingalls, it was equally obvious he had followed a very conservative course and the writer was not prepared for the discovery that in addition to the artifact mentioned, several others had been unearthed and no less than five of them preserved.

In his account of these finds, Doctor Priestly stated all had been personally made by Mr. A. H. Holloman, who owns and operates a sand and gravel pit about one mile north of the city of Frederick. To Mr. Holloman, therefore, the writer is indebted for a history of the discoveries, their stratigraphic position, and other items having a bearing on them.

|

Independent of the opportunities thus offered for studies of the exposed formations, it also made it easily possible for Mr. Holloman to point out the horizons at which artifacts and the several varieties of fossils had been found.

That a great deal of fossil material has been uncovered since the opening of the pit, there can be no doubt, but not until during the past year was an effort made to preserve any part of it. Accounts are unanimous in showing that quantities of such material have gone into the refuse heap, now comprising thousands of tons; into the surfacing of roads; the cement mixer, etc. Seven known artifacts are buried somewhere in this refuse pile or carried away: a metate and six pestles or manos, but these cannot be considered here. (The Colorado Museum of Natural History has arranged to keep a representative constantly on the ground to search for and preserve all artifacts and fossils hereafter uncovered.)

Although fossils are found throughout the entire stratum of sand and gravel deposits, a superficial study of all the evidence suggests the possibility that two faunal and cultural stages are represented. This, however, is for others to determine, and the writer will confine himself to the circumstances connected with the finding of the artifacts and to brief references to the deposits from which they were taken.

|

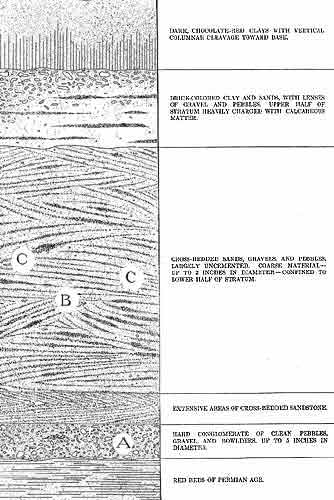

The base member, composed of clean river gravels, pebbles, and occasional boulders up to five inches in diameter, is solidly cemented with semi-translucent lime, and lies uncomformably upon red beds of Permian age. This stratum contains numerous fossils of several varieties, such as Mylodon cf. harlani, three species of Equus, Trilophodon, sp., and a primitive Elephas, etc. Associated with them and at the point marked “A,” the artifact illustrated in Fig. 6, No. 1, was found by Mr. Holloman. It is a light-gray flint, and while the flaking exhibits considerable skill, perhaps, as a whole, the workmanship is poor, with the chipping confined to the reverse sides of the edges (see cross-section, Fig. 6, No. 2). Whether or not other flints have been uncovered at this level, there is no means of determining, this single example having been picked up by Mr. Holloman as it was broken out of the hard matrix by workmen. Two stones taken at the same level and described by Mr. Holloman, can scarcely be regarded as other than pestles or grinding instruments, but subsequently these disappeared and cannot be otherwise recorded here.

Lying immediately on this hard conglomerate is a partially cross-bedded layer of coarse, lenticular sandstone, one and one-half to two feet in thickness. This appears to be, principally, at least, nonfossiliferous; but the following member, consisting of heavily cross-bedded and but partially cemented coarse sands, gravels, and pebbles, contains numerous fossils throughout its varying thickness of from nine feet to fifteen feet. (See Fig. 5.) Seven feet below its upper margin, or at the point marked “B,” the arrowhead illustrated in Fig. 6, No. 3 was found in position by Mr. Holloman. It is a pale grayish and reddish flint, mottled and slightly streaked, and of good workmanship. With the exception of an appearance of slight damage at the point, due, perhaps, to its having come in contact with some hard substance, it is quite complete.

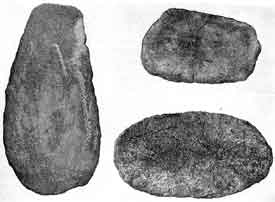

On a general average level of a foot or two above the horizon at which this arrowhead was found, not less than five unquestionable metates have been uncovered in Mr. Holloman’s presence—three of these being illustrated herewith. They are composed of a hard, close-grained, limy and silicious sandstone, the ovate depression in the largest example having a maximum depth of three-quarters of an inch. The edges of these artifacts are distinctly rounded and smooth, as is the reverse side. As it cannot be doubted that these stones show evidence of human workmanship, that they are identical in general form to metates found in other localities, and owing to the fact that no other stones of a similar nature have been found in the thousands of cubic yards of material that have been removed, there can be no question about their original purpose and use.

|

Perhaps no very great importance would be necessarily attached to these artifacts were it not for the fact that they were imbedded in ancient river channel material and that Mammoth remains, including numerous teeth, are found at various levels, to a point eight feet above them. Further, no remains of this type of Mammoth, columbi, have been found at, or below, the horizon at which the metates were exposed.

|

Reference has been made to pestles, or grinding stones. Five stones were found by Mr. Holloman at various levels from the base of the deposit to the horizon of the metates, but unfortunately these have been lost and are not of record here.

In connection with these finds, the writer desires especially to express his appreciation of the generosity extended by Doctor Priestly and Mr. Holloman, for not only did they lend every possible assistance, but donated to the Colorado Museum of Natural History all of the artifacts and fossils they had preserved. In addition to this, they aided in locating fossils in the possession of others. Mr. Holloman has also volunteered every facility for the Museum to engage actively in work in the quarry. Science owes Doctor Priestly and Mr. Holloman its appreciation.