July-August 2004

With Hands or Swift Feet

The ancient Greek city-states were rarely as united as they were at the Olympic Games.

By David C. Young

| This article has been adapted from A Brief History of the Olympic Games, by David C. Young, which is being published this summer by Blackwell Publishing. Copyright (c) 2004 by David C. Young. |

|

For the poet Pindar of Thebes, whose victory odes immortalized the greatest contenders of the Hellenic world between 498 and 446 B.C., the athletic contest served as a microcosm of the human struggle to surpass ordinary achievements.

In athletic games the victor wins the glory his heart desires

as crown after crown is placed on his head,

when he wins with his hands or swift feet.

There is a divine presence in a judgment of human strength.

Only two things, along with prosperity, advance life's sweetest prize:

if a man has success and then gets a good name.

Don't expect to become Zeus. You have everything

if a share of these two blessings comes your way.

—Isthmian Odes 5.8–15

“Don't expect to become Zeus,” warns Pindar—after all, men are not gods. But with these words he is also bestowing the greatest praise on the winning athletes, for they have reached the highest mortal pinnacle.

Archaeology tends to confirm—approximately—that the Olympics, the most renowned of the ancient contests, began when the Greeks claimed they did, in 776 B.C. The Olympics then took place every four years well into the latter days of the Roman Empire, until about 400 A.D. Their golden age, however, lasted from the late sixth to the early fifth centuries B.C., and if there was a special golden epoch of the golden age, it came with the games of 476 and 472 B.C.

| Archaeology tends to confirm—approximately—that the Olympics, the most renowned of the ancient contests, began when the Greeks claimed they did, in 776 B.C. The Olympics then took place every four years well into the latter days of the Roman Empire, until about 400 A.D. |

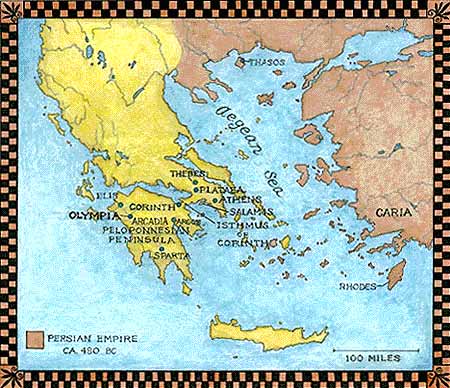

In 490 B.C. and again in 480, a large Persian army had invaded Greece, seeking to subdue it and turn it into a vassal state. The vast Persian Empire already encompassed not only present-day Iran, but also Afghanistan and Pakistan in the east, part of Iraq, and, in the west, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and northern Egypt. If the invaders had succeeded, Western history would have taken a decidedly different turn. But the Greeks expelled the enemy after the naval battle of Salamis, fought in 480 in a strait west of Athens, and the battle of Plataea, fought in 479 on the mainland northwest of Athens. It was the first time so many Greek city-states, which were often at war with one another, had banded together. A Panhellenic spirit began to surge throughout the land, most of all at Olympia, the seat of the Olympics. People flocked there in unprecedented numbers, all in jubilation. More contestants came than ever before, and the athletes of the period were among the best and best known in Greek history.

By the time of the 476 B.C. games, nearly the full complement of athletic events had been incorporated into the festivities. Present-day knowledge of them comes from the excavation of Olympia and other sites, from artistic depictions (most notably on vases and in sculpture), from contemporary inscriptions on vases and monuments, and from the various odes, histories, and other texts that scribes have copied and handed down through the centuries. The historical texts often include quite vivid and detailed descriptions. But the texts present many problems as well. Many were compiled by writers who lived centuries after the events, which they did not witness themselves; many conflict with each other (or are internally inconsistent); and, even taken together, the texts fail to clarify certain essential points. As a result, modern scholars are still sorting out and debating many issues.

The signature contest of the 476 B.C. games, as it was throughout Olympic history, was the stade, a sprinting race that was run the length of a straight track (from stade comes our word “stadium”). The distance, measured from the actual track archaeologists have uncovered at Olympia, was about 210 yards. From the very beginning of the games until the games of 724 B.C. the stade was the only recorded event. In the latter games the diaulos was added, a race of two laps, or about 420 yards. Four years later a distance race called the dolichos was introduced, though ancient sources do not specify the exact number of laps. The most widely accepted number is twelve, which equates to a race of about 2,520 yards, or a bit more than 1.4 miles.

Events became much more diverse beginning with the Olympics of 708 B.C., which included wrestling and the pentathlon. Pentathletes competed in discus, javelin, long jump, and their own stade race, and finished with their own wrestling bouts. How the overall winner was determined is not really known. In some rather rare cases, a winner was declared if a contestant won the first three events, and the contest was then finished. But more often the outcome hinged on the wrestling final.

| The main debate about the discus throw is whether ancient athletes executed a full rotation of the body, using centrifugal force to help launch the discus, as do modern competitors. |

The discuses excavated at various ancient sites are made of metal, usually cast bronze, or stone and—except for small ones possibly intended for children—weigh between four and nine pounds. The main debate about the discus throw is whether ancient athletes executed a full rotation of the body, using centrifugal force to help launch the discus, as do modern competitors. The prevailing opinion is that they used arm strength, perhaps with some body twist, but not a full spin. I disagree. I find the textual evidence at best ambiguous, but certain artistic depictions tip the balance in favor of a full rotation, because they make little sense otherwise.

The nature of the long jump has been a special a source of controversy. Much of the confusion has its inception in reports that two early athletes, Phayllos of Croton and Chionos of Sparta, jumped farther than fifty feet. A single jump of that distance is beyond credibility, and accordingly, many scholars have concluded that this Olympic event comprised multiple jumps, such as a triple running jump or five standing broad jumps. I believe such conclusions are misplaced, however, and that the event was a single running jump. First, I am convinced that both of the reports in question are false: they appear in unreliable texts dating six or seven centuries after the supposed achievements. Second, ancient artistic depictions, as well as other literary evidence, are consistent with a single running jump. Additional controversy surrounds the hand-held weights, known as halteres, that were swung upward and forward on take-off, presumably to help the jumper gain extra momentum [see “Throwing Yourself into It,” by Adam Summers, April 2003].

The Olympic javelin was made of wood; for that reason, no doubt, no example survives. Artistic evidence suggests the implement was lighter and slightly shorter than the standard modern javelin for men. A short leather thong was wrapped around the middle of the shaft and secured with a loop to the thrower's fingers. As the throw was made, the thong was allowed to unreel, extending the effective point of release and imparting a spin that made the javelin fly farther and truer than it would without the thong.

Wrestling, both for the pentathletes and for the single-event competitors, was a contest of strength, balance, and technical know-how. The object was to throw the opponent so that his back, hip, or shoulder touched the ground. Victory went to the first man to achieve three falls. Wrestling was the one athletic activity practiced by almost all freeborn men in Greek society, and it was a rich source of metaphor for playwrights, orators, and philosophers. Authors could assume their audience was knowledgeable about the techniques employed.

New Olympic events were introduced shortly after wrestling and the pentathlon. Boxing was added in 688 B.C., and the tethrippon, a four-horse chariot race, followed in 680 B.C. Boxers wound leather thongs around the forearm and hand; the fingers were left open. Once two competitors faced off, they would continue fighting until one of them could no longer continue or formally admitted defeat. All the punches appear to have been directed at the head. Olympic history records the deaths of several boxers—though surprisingly few overall, given the brutality of the contest.

| Wrestling was the one athletic activity practiced by almost all freeborn men in Greek society, and it was a rich source of metaphor for playwrights, orators, and philosophers. Authors could assume their audience was knowledgeable about the techniques employed. |

In the tethrippon and other horse races, the charioteer or jockey was a professional, but the owner—who was, of necessity, a rather wealthy person—enjoyed the honor of victory if it came. Equestrian events were the only ones in the Olympic Games that women could—and did—win. Teenage girls and young women apparently had very few athletic contests of their own in the ancient Greek world, perhaps only in Sparta. At least during the Roman Empire, they did participate in events at Olympia, but their contests did not fall at the same time as the Olympic Games.

Were women allowed to watch the games? The relevant evidence remains murky. Pausanias, a Greek traveler and geographer who lived in the second century A.D., reports that women were banned from becoming spectators, and that violators were to be thrown to their deaths off a cliff. But Pausanias also asserts that the punishment was never invoked. And elsewhere, he even seems to contradict himself. After referring to a special seat from which the priestess of Demeter watched the games, he writes: "They [the officials] do not prevent unmarried women from watching."

Much has been made of the distinction Pausanias makes between married and unmarried women. But it seems out of context. In my view, some later scribe inserted the sentence while copying the text, thinking it clarified why the Greeks allowed the priestess to watch the games. The scribe was probably assuming that a proper priestess had to be a virgin, but in fact, the priestess of Demeter was invariably a married woman. Even if women were not altogether banned from the Olympics, chances are that few could have attended, unless they were local inhabitants.

No doubt one reason this side issue evokes such interest today is that the Olympic athletes competed in the nude—even the jockeys, who rode bareback. (The only exceptions were the charioteers, who wore long, white gowns.) In modern Western culture, the idea that female spectators watched the competitions of naked men is titillating or scandalous. But nudity in itself was not so remarkable to the ancient Greeks, nor did it evoke the same reactions (they wondered why "barbarians"—non-Greeks—thought it embarrassing or shameful). Nudity also had the practical advantage of making it easier to massage and oil the body, both integral parts of athletic training.

Among the other notable events that had swelled the festivities by the time of the 476 B.C. games were the pancration, or no-holds-barred fighting (all manner of wrestling holds, kicks, and blows were permitted; only eye-gouging and biting were prohibited); the hoplites, a two-lap race in which each runner wore a helmet and carried a shield; a horse race; a mule-cart race; and contests for boys (stade, wrestling, and boxing). Only a few events were added later on: a pancration for boys, competitions to select the official trumpeter and herald, and some additional equestrian events.

The Olympic Games were attached to a festival in honor of Zeus, and may have originated with contests among pilgrims who had come to take part in the god's cult. But by 476 B.C., indeed much earlier, religious fervor was not what drew athletes to Olympia. Money no doubt was a factor. Although victors received no prizes of value at Olympia itself, just the olive crown, winning was frequently a ticket to high profit from other sources. The cities from which the athletes came often bestowed cash payments on their champions. Still, for the best athletes the main incentive was the pursuit of excellence in itself, to compete and win at the highest level, with all the fame and glory that bestowed.

| Pausanias, a Greek traveler and geographer who lived in the second century A.D., reports that women were banned from becoming spectators, and that violators were to be thrown to their deaths off a cliff. |

The ancient Greeks kept no records in the modern sense; they never measured performances in meters and minutes (for one thing, they lacked stopwatches). But they did keep records of other kinds: Who was the first to win a particular combination of events? Who won the greatest number of victories in a particular event? The first-known runner with multiple victories, for instance, was Pantacles of Athens, who won the stade in 696 and 692 B.C. Chionis of Sparta won both the stade and diaulos for three Olympiads in a row, in 664, 660, and 656 B.C. In 480 B.C., Astylos, representing Syracuse, Sicily, not only matched Chionos by winning for a third time in the stade and diaulos, but also demonstrated his versatility by winning the hoplites, the race with armor. (Defending the honor of their countryman, the Spartans added to the inscription on Chionos' memorial stele in Olympia, pointing out that there was no hoplites event in his time.)

Astylos' record stood for three centuries, until Leonidas of Rhodes won those three races for four Olympiads in a row, from 164 until 152 B.C. After that, what record could an athlete aspire to? Polites of Caria (a region in what is now southwestern Turkey) trained for the stade and the long-distance race, defying the odds that a runner could excel both in sprinting and endurance. He won both on the same day, in 69 A.D.

At the games of 476 B.C., there was special interest in boxing and pancration. Euthymos of Epizepherian Lokris, a Greek colony in southern Italy, sought to regain the boxing crown he had lost to Theogenes of Thasos in the previous (480 B.C.) Olympiad. In that earlier Olympiad Theogenes had also qualified for the pancration final, but he had become so exhausted from his boxing victory over Euthymos that he did not compete in the pancration. Olympic officials fined him for forfeiting the event and disqualified him from the boxing contest in the 476 B.C. Olympiad. Euthymos took advantage of his rival's absence and won the boxing in 476. Theogenes won the pancration, however, allowing him to proudly claim a record: “First man ever to win both boxing and pancration at the Olympics.”

The 472 B.C. Olympiad was marked by an extraordinary upset when a civic entry owned by all the citizens of Argos won the chariot race. In what must have been an exciting contest, they defeated the winner from the 476 games, Theron, the king of Acragas, an important Greek city in Sicily. The victory finally broke the elitist monopoly of that expensive event.

The cult of Zeus at Olympia during the 476 B.C. games was the happy recipient of many valuable donations, as people and states dedicated their booty from the Persian War to the god. Elis, the loose confederation of neighboring villages that hosted the Olympics, gained new affluence, and the Eleans finally built themselves a true town. An ambitious building program also began at Olympia. The stadium was moved slightly, and both the track and the spectator facilities were improved.

Within twenty years of the 476 games, a new temple to Zeus was completed. It measured about 100 feet wide, 230 feet long, and seventy feet high, and was roofed with the finest marble, topped by a golden statue of Nike, goddess of victory. For four years beginning in 437 B.C., the Athenian sculptor Pheidias directed the construction of a forty-foot-high statue of Zeus, seated on his throne inside the temple. Marble or cast bronze would have been too heavy for such an enterprise, so Pheidias made it of gold and ivory plates over a wooden framework. A system of pipes was devised for carrying oil to the wood, to keep it from rotting. The oil also helped to preserve the ivory for more than seven centuries. The statue has not survived, yet it is still famed as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

But by the time it was finished, the statue was already a relic of another age. Flush with their united victory over the Persians, in 476 B.C. the Greeks had moved to end wars among themselves. Many of the Greek city-states agreed to allow Olympic officials to form a kind of judicial appeals board, which would settle political disputes by arbitration instead of by arms.

Within a few years, though, the member states ceased to recognize the authority of the Olympic appeals board, and no longer submitted cases to it. Hostile actions began taking place until the region fell into the Peloponnesian War of 431–404 B.C., one of the bloodiest and cruelest in ancient history.

The Roman emperor Nero decided that he himself should participate in the chariot race in 67 A.D. Nero fell off his chariot but claimed victory anyway, and the olive crown was presented to him by the bribed and terrified judges. |

Eventually, though, even the Olympics fell victim to hostilities. In 364 B.C., an army from the region of Arcadia (the Eleans' traditional foe) invaded Elis and occupied Olympia. When it was time to hold that year's games, the Arcadians usurped the role of sponsor. In retaliation, the Elean army invaded Olympia, arriving while the wrestling final of the pentathlon was in progress. The armies joined the battle immediately, reaching into Olympia's most sacred precincts. They fought into the night, the Arcadians and their allies occupying the roofs of the buildings and raining missiles down upon the Eleans. The Eleans were driven back, and the games were completed. Subsequently a multinational truce gave Olympia back to Elis, and the Eleans hosted the 360 B.C. games as usual.

The Olympics underwent their biggest ups and downs after the Romans took over Greece, in 146 B.C. Augustus, who effectively became emperor in 27 B.C., subsidized Greek athletics and saw to the renovation of the stadium at Olympia. In contrast, the notorious Nero decided that he himself should participate in the chariot race in 67 A.D. Nero fell off his chariot but claimed victory anyway, and the olive crown was presented to him by the bribed and terrified judges. (Not long afterward, Nero was assassinated, and the results of the 67 games, including Nero's “victory,” were voided.) The Olympics enjoyed a renaissance in the second century A.D., once again drawing many athletes and spectators and sparking renewed building at Olympia. But after the games of 217, interest in the games steadily declined.

Although the names of many of the later Olympic victors have not come down to us, just ten years ago a large portion of a bronze plaque was unearthed at Olympia, which lists some winning athletes from the first century A.D. to almost the end of the fourth. The last two entries are for two brothers from Athens: Eukarpides won the boys' pancration in 381, and Zopyros won boys' boxing in 385.

Combining an academic specialty in ancient Greek poetry with a lifelong enthusiasm for sports, David C. Young has spent many years investigating the Olympics, both early and modern. Young's article in this issue is based on his new book, A Brief History of the Olympic Games, which is being published this summer by Blackwell Publishing. His previous works include The Olympic Myth of Greek Amateur Athletics (Ares, 1984) and The Modern Olympics: A Struggle for Revival (Johns Hopkins, 1996). Young is a professor of classics at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

Copyright © Natural History Magazine, Inc., 2004