Featured Story

![]()

June 2007

![]() Bones from the Tar Pits

Bones from the Tar Pits

![]()

La Brea continues to bubble over with new clues

about life that flourished 40,000 years ago,

where Los Angeles is today.

![]()

By John M. Harris

![]()

Right: cleaned skull of a saber-toothed cat

![]()

Photo © John M. Harris

We have dredged and scraped, on hands and knees, to a depth of fourteen feet, where the air is redolent with sulfurous hydrocarbons. Our excitement mounts as we expose the skull of a saber-toothed cat, entombed in the asphalt. This site, Pit 91, lies within one of the richest pockets of Ice Age fossils in the world, and those of us working the pit collect thousands of bones and hundreds of gallons of surrounding material every summer. Finding a saber-tooth here is common, yet every skull continues to be special. Will this one have its canines? Its lower jaw?

The skull turns out to be nearly complete. One summer as long ago as 40,000 years, the great cat might have ventured onto uncertain ground to feed on an easy target, a bison perhaps, mired in the sticky asphalt, or “tar.” The temptation would be the cat’s last. When the saber-tooth attacked, its fate—along with the bison’s—was sealed. It and literally thousands of other animals have become trapped at a unique spot that paleontologists now comb for remnants of ancient life.

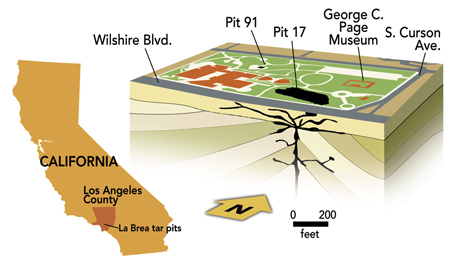

With the discovery of the saber-tooth our dedicated band of tar-stained volunteers takes a brief pause, but soon they are back at work, painstakingly continuing the excavation of Pit 91. The justly famous La Brea tar pits lie just seven miles west of downtown Los Angeles, in what is known as Hancock Park, where Pit 91 is the last active excavation [see map below]. The volunteers work under the guidance of Christopher A. Shaw, the collections manager for the George C. Page Museum, which was built by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in 1977 to house fossils from the tar pits. Shaw keeps the excavators following a rigorous procedure not unlike the one initiated here by paleontologists in the early 1900s. (Boiling kerosene, though, no longer serves to clean the sticky bones—nor does it accidentally catch fire and singe the eyebrows of workers.) Shaw’s volunteers clear square grids three feet on a side and dig down through the layers six inches at a time, all the while coping with the thick asphalt bubbling up around the bones.

|

||

In spite of those challenges, the excavation pours out the remains of fossils from the late Pleistocene epoch, between 27,000 and 40,000 years ago, some of which may be completely new to science. Since the current excavation began in 1969, more than 320 species have been added to the 270 or so that were first collected here ninety years ago. Together they provide a detailed picture of ancient life in the Los Angeles Basin, from giant mammals down to water fleas.

Real tar, technically, is a product distilled from wood, coal, or peat, whereas the sticky black “tar” responsible for the rich accumulation of fossils is natural asphalt made up mostly of crude petroleum. It oozes up through natural plumbing in the Earth’s crust from the Salt Lake Oil Field, about 1,000 feet below the surface of Hancock Park. More petroleum has collected even farther down—as deep as 10,000 feet underground—in 5-million-year-old rock, which helps feed the current asphalt seeps. The pressures at such depths have squeezed crude oil, natural asphalt, and methane gas to the surface for at least the past 50,000 years. Similar sites have been discovered in Asia, the Middle East, South America, and elsewhere. One exciting asphalt seep in Venezuela has recently been coughing up ancient armadillo fossils.

In California, people collected the asphalt from the tar pits long before its fossil content was discovered. Native Americans began using it in prehistoric times as a caulk for baskets and canoes. Early settlers in Los Angeles used it as a fuel and as waterproofing for their roofs. In 1828, when southern California was still part of Mexico, the Mexican government included the current La Brea pits as part of a land grant known as Rancho La Brea (Spanish for “the tar ranch”), which stipulated that the landowner must permit Angelinos to retrieve as much tar as they needed for personal use. By the late nineteenth century, asphalt from La Brea fetched twenty dollars a ton after it was refined for various purposes, including road building.

| ||

Bones recovered in those early collections were dismissed as the remains of domestic animals. It was not until 1875 that the geologist William Denton visited the tar pits and identified the canine tooth of a saber-toothed cat. Denton reported his find, but the rest of the scientific community took little notice. No one bothered with any large-scale recovery of the fossils until after 1901, when William W. Orcutt, a geologist who was investigating oil resources in the vicinity, noted that the bones in the asphalt seeps belonged to many extinct species.

Suddenly the tar pits became all the rage, as amateurs and institutions competed for the fossil treasures. Excavation peaked at Rancho La Brea between 1905 and 1915, when literally millions of bones were taken out of the ground. In 1913, the landowner, George Alan Hancock, finally acted on his fears that the fossils would be taken from the community and scattered widely; he granted exclusive rights to excavate the fossil resources to Los Angeles County’s fledgling Natural History Museum—but only for two years.

The museum took full advantage of its brief time window. Between 1913 and 1915, museum crews intensively explored the twenty-three acres of the area that would become Hancock Park, making nearly a hundred excavations and collecting roughly a million bones. Hancock later donated that part of his property to the county, with instructions that the tar pits be preserved and appropriately displayed.

The spectacular array of fossils from the 1913–15 excavations were subsequently housed in the basement of the Natural History Museum. They included carnivorous saber-toothed cats,

|

||

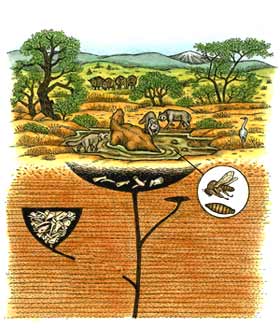

What makes the tar such an effective and deadly animal trap? In the warm summer months the asphalt reaching the surface becomes viscous and sticky, and so it quickly acquires a deceptive surface covering of dust and leaves. Cows and horses have been observed in modern times wandering across oil seeps, where an inch or so of sticky asphalt is all it takes to totally immobilize them. Similarly, Pleistocene herbivores inadvertently stepping into the edges of the La Brea seeps would have found themselves held as fast as flies on flypaper—vulnerable to starvation, dehydration, and predatory attacks.

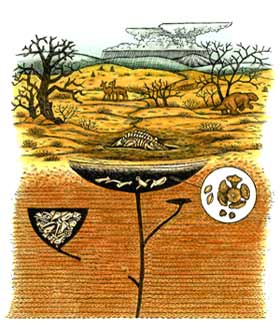

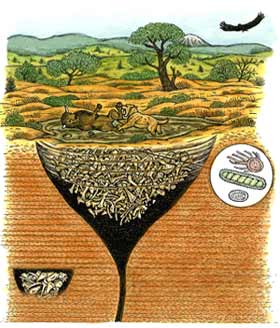

As cool winter temperatures returned, the asphalt would resolidify, sealing in the summer’s bones. Winter winds and rain would further cover the surfaces of the seeps with sediment washed down from the nearby Santa Monica Mountains. Then, once temperatures warmed up in the spring, the seepage would start again, and the trap would reset. For a few thousand years, masses of tangled bones would accumulate in conical pits on the rising coastal plain, until the existing vents became blocked [see illustration below]. Most of those accumulated bones, paleontologists found, were carnivores; in fact, they outnumbered herbivores by almost nine to one. The bird species, too, were primarily birds of prey. Such an abundance of carnivores at La Brea led to the entrapment hypothesis: that mired animals served as bait for predators and scavengers.

In the half century that followed the initial description of the Rancho La Brea fossils, it became apparent that crucial information was missing. The museum excavators had concentrated on the trophy specimens—the lions, mammoths, and saber-toothed cats—and had largely ignored smaller fossils such as rodents, seeds, and snails. Paleontologists now recognize that the smaller fossils often provide the best evidence about the habitats and environments in which the fossils accumulated. Larger creatures may have wandered for miles during their lives, whereas the small mammals and insects probably never strayed more than a few hundred feet from where they were trapped.

| ||||||

So in 1969 the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County began another excavation, focusing on Pit 91, which had been discovered in 1915. County museum staff had left the mass of bones in place, hoping for a future exhibit that would show park visitors how the fossils were found in the ground. Fortunately for science, the bone mass remained undisturbed in the ensuing years. And on Friday, June 13, 1969—“Asphalt Friday” of Page Museum lore—the excavation of Pit 91 began.

The new excavation has added 131 plant species, 88 insect species, 63 mollusk species, and 18 small-mammal species to the menagerie of Rancho La Brea. Moreover, the masses of bones from Pit 91, cleaned and cataloged, helped to prepare a test for the entrapment hypothesis. I took part in that project with Lillian Spencer, an anthropologist at Arizona State University in Tempe; Blaire van Valkenburgh, a paleobiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA); and a team of UCLA students. Together we studied 18,000 bones and found, first of all, that the great majority of them showed little or no weathering.

| ||

What about other markings on the bones? If the asphalt seeps acted as carnivore traps, with mired animals as bait, one might expect to find tooth marks, for instance. Yet of the 18,000 bones, only 2 percent had been scored, notched, or punctured by carnivores, and 76 percent of the adult bones were complete. Nevertheless, our study also noted that many bones from ground sloths, ruminants, and deer were so fragmentary they could not be properly identified. Those bone fragments had probably been scavenged and crushed by predators near the asphalt seeps. The unmarred bones were probably from parts of the carcasses too mired in asphalt for carnivores to disturb.

The skeletal proportions of the trapped animals provide further, telling evidence of scavenger activity. Carnivores at kill sites often remove a limb from a carcass and carry it to a safer place for feeding. A tally of each of the seven most common species at Pit 91 showed that for every skull in the sample there was only one forelimb and one hind limb. The missing limbs provide strong circumstantial evidence that mired animals were ravaged by carnivores. The skeletal remains also show that not all species were equally attractive to scavengers. For horses, more than 75 percent of the limb bones were represented, whereas among bison, more than half the limb bones were missing. The bison bones also tended to be less complete than those of the horses. Spencer, van Valkenburgh, and I think those data show that carnivores preferred bison limbs, probably because of their greater fat content.

|

||

Our interpretation recently gained support from work I undertook with Joan B. Coltrain, an archaeologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Features of an animal’s diet and local environment can be inferred from the proportions of stable isotopes in its remains. For example, the ratio of nitrogen-15 to nitrogen-14 changes from species to species when moving up the food chain, providing a clue as to who is feeding on whom. By analyzing the nitrogen-isotope ratios in bones from Rancho La Brea, we found that the coyotes were omnivorous; that the dire wolves and lions were feeding on horses, ground sloths, and ruminants (but not on mastodons); and that the saber-toothed cats preferred bison and camels.

The asphalt continuously seeping into Pit 91 has been a constant problem for the excavators, but the muck, even without bones, has opened up an unexpected line of research. A recent study by David E. Crowley and Jong-Shik Kim, both microbiologists at the University of California, Riverside, revealed that hundreds of species of bacteria and archaea also thrive in the asphalt seeps. One key part of the microorganisms’ adaptation to life in the asphalt is that they “eat” petroleum: they grow by breaking down petroleum hydrocarbons, which they incorporate into their cells.

The discovery of such microfauna has enormous potential for biotechnology. To take just a few examples, understanding their biochemical pathways could lead to new medicines, polymers, and petroleum-based biodegradable plastics. If some of the microorganisms can be isolated from the asphalt and grown in the laboratory, they may be effective in treating oil wastes and contaminated soils.

At the present work rate, the excavation of Pit 91 could take another ten to fifteen years to complete. In that time, continuing research on the microorganisms could lead to an efficient way to clean the backlog of bones at La Brea—not to mention fossils from other asphalt seeps around the world. If that comes to pass, a lot of storage containers at La Brea undoubtedly hold the bones of new species—as well as trusty saber-tooth skulls—that will finally get the cleaning they deserve.

| Hear author John Harris interviewed by Peter Brown, Editor-in-Chief of Natural History. (MP3, 15.5 minutes) | |

John M. Harris was trained as a geologist and served as the director of paleontology at the National Museum of Kenya before joining the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in 1980. He now works there as chief curator of vertebrate studies and oversees the vast collection of late Pleistocene fossils from the La Brea tar pits, housed at the George C. Page Museum. Although he has published widely on La Brea, he is perhaps better known scientifically for his work on East African ungulate fossils associated with the remains of early hominids. He edited a book with the paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey on the fossil footprints of Laetoli, Tanzania, and another with the paleoanthropologist Meave Leakey on the fossil site of Lothagam, Kenya. |

- Web links related to this article:

![]()

Copyright © Natural History Magazine, Inc., 2007